Suzuki's New Turbo Secrets

Suzuki look set to unleash a production version of the turbo-charged Recursion concept bike.

The latest patents filed by the firm suggest it will be a seriously well-engineered machine with the potential to bring turbos back to the fore in motorcycling for the first time since the spate of ill-judged offerings in the mid-1980s.

Earlier this year, Suzuki dismissed talk of a production bike as speculation, but bosses were careful not to rule out the idea with Suzuki GB General Manager Paul de Lusignan saying: “The concept made its first UK appearance at Motorcycle Live 2014, where we gathered feedback on the styling and technologies involved to help the factory with planning and development.”

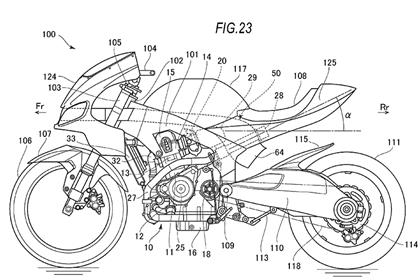

The latest patent suggests a production model is indeed under development, since it features elements that wouldn’t be needed for a show-only bike, and reveals detailed changes to the design including a new intercooler, which in turn requires a new headlight design.

More than that, the patent gives the first in-depth look at the technology of the Recursion’s 588cc parallel-twin and the attached turbo system.

Big low-down torque

Official information from the bike’s unveiling at the Tokyo Motor Show in October 2013 claimed that it used a 588cc parallel twin with a single turbo boosting power to a claimed 99bhp at 8000rpm. A respectable, but not headline-making, figure. What is impressive is the torque, claimed to be 74ftlb at 4500rpm. That’s the sort of figure that 1000cc superbikes achieve, and the Recursion does it at half the revs and from little over half the capacity.

The new patents reveal that the engine is a single-overhead-cam design, which makes it lighter and more compact than a DOHC motor. Since high revs aren’t needed, there’s little to be gained from adding another camshaft. Sadly there are no internal pictures revealing whether the engine uses two valves per cylinder or has a rocker system to operate four valves per cylinder.

Unlike Kawasaki’s supercharged H2, the Suzuki uses an intercooler to make the intake air colder and denser before it reaches the engine. The intercooler is an air-to-air design, fitted underneath the rider’s seat.

The turbo itself is low down at the front of the engine, as close as possible to the exhaust headers to help reduce lag. It sucks air in via a pipe going to an air filter in a box next to the rider’s left foot, compresses it and forces it back through a pipe around the left side of the engine to the intercooler – effectively a radiator where instead of water the air itself is cooled by running through large pipes covered in fins that help dissipate heat. Here the intake air makes a U-turn and comes back to a compact sealed plenum chamber (a pressurised airbox) attached to the throttle bodies of the engine.

The pictures show that the intercooler is nearly as large as the bike’s radiator, and that in turn suggests that there’s a fairly high level of boost being used – the more air is compressed, the hotter it gets, so a larger unit is needed.

Meanwhile, the exhaust gasses that have worked to spin the turbo at something like 200,000rpm are fed out through a pipe on the right hand side of the bike, into a silencer and catalytic converter under the engine.

Intercooler dictates styling

The images in the new patent reveal that where the concept had a stacked headlight, in reality the intercooler will need to be fed a large amount of cooling air from an intake in the centre of the nose where that headlight originally resided. The patent reveals a new front-end style with a central air intake flanked by twin headlights.

That intake feeds air into a sealed tube that splits to run around the steering stem before going over the top of the engine, between the frame rails, and sealing onto the top surface of the intercooler. Suzuki are effectively using the ram air effect of the high pressure spot on the nose, usually used as an engine air intake.

Having passed through the intercooler, that air needs to vent and the patent shows three possible designs to help it do that. One is simply a short outlet pipe, exiting the bodywork below the seat just ahead of the rear wheel, while the other two reveal more extreme designs that pipe the air right back to the tail of the bike – one shows a rectangular exit, while another opts for a pair of circular vents. These extended vents are likely to help cool the intercooler because they use the aerodynamic low-pressure area at the very back the bike to help suck air through the system.

The set-up means that the fuel tank needs to be in a very traditional spot, carrying petrol high above the engine. The intercooler and its plumbing mean there’s no scope to have the tank extend down under the seat, but the lack of a traditional airbox means the area above the front of the engine can actually be used for fuel instead.

Suzuki’s playing it safe

Suzuki are concentrating on the turbo as the bike’s main feature. There’s no semi-auto transmission or oddball suspension system to cloud the issue; Suzuki knows that asking riders to adapt to a turbocharged engine is a big enough step without adopting other radical ideas.

Why turbos are the future

Modern turbos are all about efficiency – allowing more fuel and air to be burned in a single stroke – without the losses associated with high-capacity engines. Big, powerful normally-aspirated engines struggle with pumping losses whenever the throttle isn’t wide open – the effort of sucking air through the small throttle opening is significant and seriously affects their emissions and economy at low speed. Meanwhile, high-revving engines have larger friction losses than lower-revving designs. A turbo allows manufacturers to make small, low-revving engines which can offer improved emissions and economy at partial throttle openings while still achieving impressive performance when the power is wound on.