Suzuki GSX-R750 special - Old v New tech analysis (Part 2/3)

Tale of the tape: very old v very new. One GSX-R is rock steady, the other isn’t. We got out the tape measure to discover why…

![]() hirty years and more separates the first and latest GSX-R750 – and the differences encapsulate the evolution of sportsbikes

hirty years and more separates the first and latest GSX-R750 – and the differences encapsulate the evolution of sportsbikes

![]()

Aerodynamics

1985: headstock height 894mm

2016: 759mm

The new bike is wind tunnel tested, and also carries a lot of experience gained in racing. The big difference is frontal area: the 2016 bike steering head is 139mm lower, and the top of its front tyre is 16mm nearer the ground too. It’s also got a faired-in headlight, lower screen, and 21mm higher seat, which cleans up the air flow over your back when you’re crouching down.

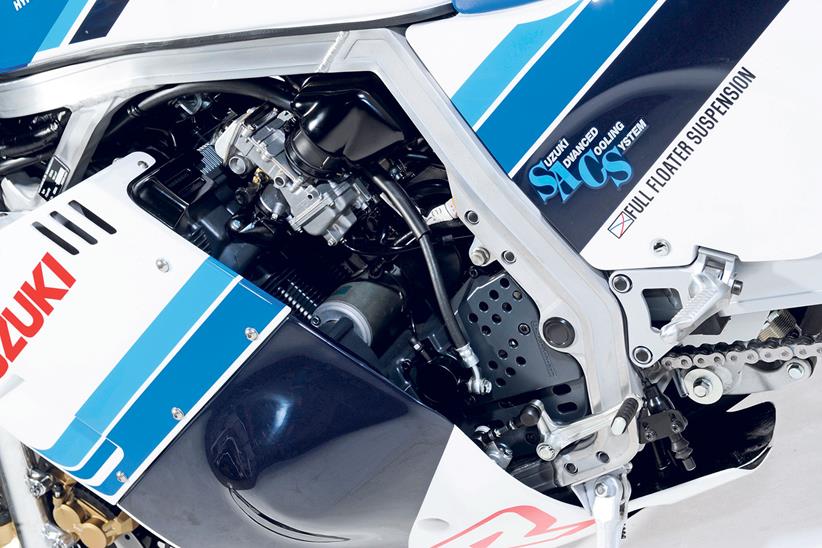

Basic layout

1985: cradle frame, airbox behind carbs.

2016: beam frame, airbox above injectors

Despite the F’s impact when it first appeared, its overall design faced more backwards than forwards. The frame used a relatively new material – aluminium – but was still designed as a cradle to house the engine, rather than a means to transmit steering inputs from the headstock to the swingarm pivot. And the engine was restricted by a traditional intake path brought about by a hemmed-in airbox and upright carbs. Yamaha’s 1985 FZ750 had already solved both these problems.

![]()

Fork design

1985: 41mm damper rod

2016: 41mm usd Big Piston

By 1985 it was common knowledge that fork tubes needed to be stiff. The snag was making them so. The old bike’s conventional legs relied on 41mm steel tubes to resist bending under braking. Today’s bike also has 41mm tubes, but in an upside down design. The braking forces are largely handled by 50mm aluminium outer tubes, carried much closer to the ground so they bend less.

![]()

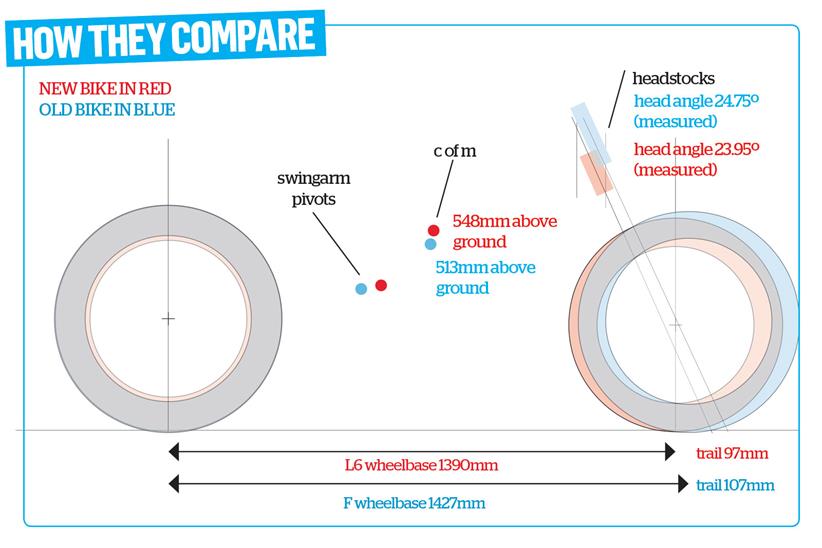

Head angle

1985: 24.75°

2016: 23.95°

Another surprise: the electronic protractor shows the two bikes are within 0.8 degrees of each other. The old GSX-R was pretty radical for its day. Its big front wheel kept it calm most of the time, but it could get slappy. The new bike, equipped with a steering damper, is far more stable.

Fork stiction

The new GSX-R isn’t just shorter, stiffer, lighter and more direct; all the details are better too. We investigated the internal friction in both bikes’ forks. The trick is to measure the length of the exposed chrome leg twice – once after pushing the forks down and letting them return, and again after lifting them up and letting them return. The difference in the two figures (anything under 8mm is good) gives an idea of the internal friction. Surprisingly there wasn’t much in it: 5.5mm new, 4.1mm old. That speaks volumes for Nathan Colombi’s rebuild.

Swingarm

1985: 529mm

2016: 583mm

Back in 1985, if a swingarm was aluminium that was almost enough. It wasn’t until 1994 that Suzuki added significant bracing. Today, the L6 uses precision casting to cut weight and add stiffness. It’s also 54mm longer, even though the wheelbase is 37mm shorter. That’s because the new bike has an inclined engine with a stacked gearbox, to minimise its front-to-rear length and get weight forward. A longer swingarm reacts less to chain pull forces, helping stability. You can gun the L6 banked over on bumps and it stays composed.

![]()

Wheelbase

1985: 1427mm

2016: 1390mm

You would think the F, with its 37mm longer wheelbase, had more stability. But the L6 beats it by having shorter load paths through the (far stiffer) chassis and wheels, higher quality suspension and vastly superior tyres.

Centre of mass

1985: 719mm in front of rear contact patch, 513mm above ground

2016: 727mm, 548mm

Centre of mass is the point through which all the forces on the bike can be said to act. It has a critical effect on traction (as the bike pitches under braking or acceleration) and stability. A typical modern sportsbike’s c of m (with a full tank) is level with the rear wheel rim, and slightly forward of half way between the axles. Adding a rider raises it level with the rear tyre, and nearer the centre.

The 1985 GSX-R’s c of m is surprisingly close to the latest bike’s. But there is a difference: the new bike uses experience developed in the early MotoGP years to cluster most of the heavy stuff near the centre of mass. The old bike is a lot more spread out. You feel it instantly when you try and change direction quickly. The new bike can do it; the old bike can’t.

![]()

Engine

1985: 10,500rpm/83bhp

2016: 13,200rpm/130bhp

The two bikes share a bore and stroke of 70mm x 48.7mm. Suzuki tried a 73mm bore in 1988/89, and 72mm in 1996-2005, but otherwise they’ve stuck to the original dimensions. So how did they get 26% more revs? Lighter components. Gradually, by shaving a few grams here and there, a factory can reduce the mass of the key moving parts – valves, piston and conrod – so they can be accelerated and decelerated more quickly, and still stay reliable. Apart from titanium valves in the new bike, the materials for the other two components have hardly changed in 30 years.

Words: Rupert Paul Photos: Mark Manning