HRC's greatest bikes: The rarest, sexiest V4 of all

Back in the late 1980s Honda made a final bid for racetrack glory with its oval-piston V4 engine. The ultra-rare NR750 racer was built to publicise a new range of road bikes that never made it into production.

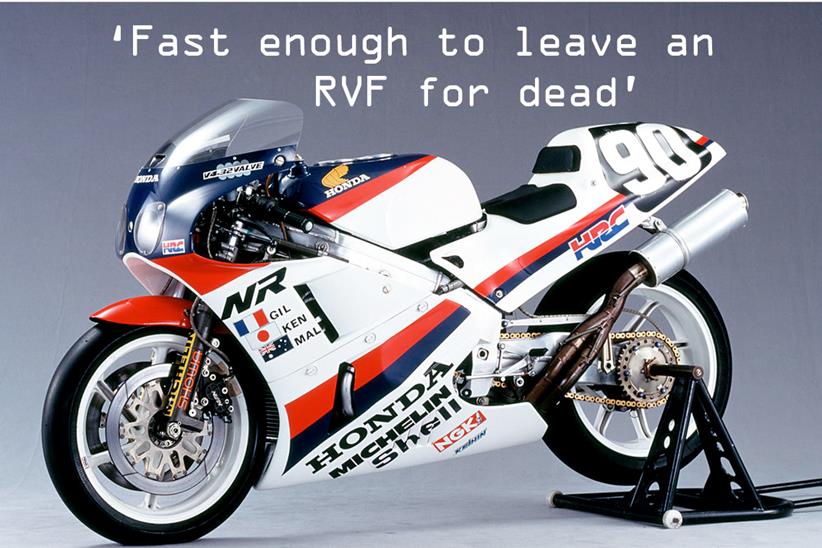

![]() as there ever been a race bike rarer than Honda’s NR750? HRC built only two examples of the oval-piston racer, which made the factory’s legendary RVF750 F1 machine and NSR500 Grand Prix bike seem common as muck.

as there ever been a race bike rarer than Honda’s NR750? HRC built only two examples of the oval-piston racer, which made the factory’s legendary RVF750 F1 machine and NSR500 Grand Prix bike seem common as muck.

The NR was the most powerful and most technologically advanced four-stroke racer of its time and yet it only contested two events – the 1987 Le Mans 24 hours and the Swann series of the same year – before disappearing from view, never to be seen again, except in Honda’s museum. So, what was Honda thinking? Why did the world’s biggest bike brand spend a fortune creating this astonishing motorcycle, then bury it?

At the time the popular theory went like this: the NR750 existed for one reason: corporate pride. It was designed to save face, to create a happy ending to an earlier story that had ended badly, and to show the rest of the world that Honda was in another world when it came to high-technology. There were also rumours of a road bike, but nothing more than rumours. Back in the late 1970s Honda had re-entered Grand Prix racing after a dozen years out of the sport. By then GPs were entirely dominated by two-strokes, but Honda was a four-stroke company through and through. Building a two-stroke GP bike would have been sacrilege.

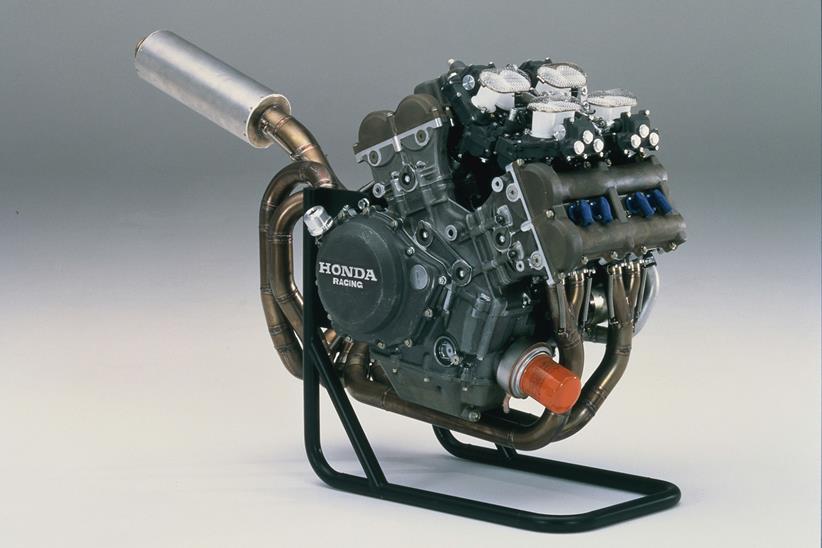

The problem was how to overcome the two-stroke’s inherent advantage of twice as many power strokes. Honda’s answer was to dramatically improve the four-stroke’s breathing, by increasing valve area. An oval piston (in fact, an NR piston was shaped more like a tin of Spam) would allow eight valves per cylinder, making a V4 work more like a V8. At least that was the theory. The reality was very different. The NR500 V4 – 32 valves, eight con rods, eight spark plugs and eight throttle bodies – cost Honda vast amounts of money but in three seasons of GP racing it never got close to winning a race, in fact it never even scored a single World Championship point. Over-the-counter Suzuki RG500 two-strokes were faster.

60 hour engine-build

The NR500 was also hideously complex, requiring no less than 60 hours of hard graft to build one engine. At some races Honda employed two shifts of mechanics – one working at the track by day, the other working by night and in secret at a nearby workshop – to keep on top of maintenance. Towards the end of the project Honda were so desperate for success that they took various NR parts to be blessed in a Buddhist shrine. Not surprisingly, the blessing didn’t work. Honda copped a lot of flak for the NR, even though the machine introduced important new technologies to motorcycling – slipper clutches and carbon-fibre parts to name but two. The bike was christened the ‘Nearly Ready’ by onlookers, then the ‘Never Ready’ and was eventually laughed out of the paddock.

![]()

Embarrassed by the NR’s failure, Honda went with the two-stroke flow and built the NS500 triple that soon won the company’s first 500 World Championship. The world had moved on and the NR was forgotten as the NS500 and then the NSR500 two-strokes ruled the world. But Honda had not forgotten the NR. The company still believed in the technology and was desperate to prove that the oval-piston concept was a winner.

In the early 1980s Honda bosses convinced the FIM to allow turbocharged 250s into 500 GPs and built an NR250 turbo. HRC squeezed an amazing 150 horsepower out of the little twin, but the engine was a grenade on the dyno and was never even seen by its intended rider, Freddie Spencer. Next, HRC came up with the idea of the NR750 – a 750cc oval-piston V4 in an RVF chassis. Only one problem: a prototype 750 wouldn’t be eligible for many races.

Le Mans

The Le Mans 24 hours was one race where the NR would be welcome, so Honda hired multiple Australian superbike champ Mal Campbell and journalists Gilbert Roy and Ken Nemoto to ride the bike. This was a PR venture to convince people of the viability of the oval piston, not an all-out attempt to win the race and beat Honda’s RVF750-mounted endurance pros.

The NR was mega-fast, making over 150 horsepower in detuned endurance trim, a good 20bhp more than an RVF.

![]()

“The bike was a fairly daunting thing because she was a fair step up in horsepower compared to what we were used to,” recalls Campbell, a teak tough Tasmanian who first tested the bike at Australia’s Calder Park two months before Le Mans. “But she was a pretty sweet thing to ride. The power was very linear and the midrange was very, very good – that’s where she was really strong. You’d be a long way out of a corner and she’d start to pull the front up nice and slow as the power came on stronger and stronger. We put a lot of mileage on the thing at Calder, that’s what HRC wanted, plenty of miles.”

Campbell adored the NR because its stonking mid-range made it perfect for the special demands of endurance racing. The unique breathing capabilities of the 32-valve 85-degree V4 gave the bike a powerband twice as wide as other four-stroke racers of the time. The NR produced huge power from 8000 to 15,000rpm which made it easy to ride, even when going off-line to duck past backmarkers. And the flat, linear spread of power gave amazing throttle feel, allowing riders to lay rubber out of every turn. Not only that, the NR was devastatingly fast, fast enough to leave an RVF for dead in a straight-line.

Vindication

While the NR500 had suffered humiliation at the hands of the two-stroke, the 750 seemed to prove that Honda’s oval-piston concept did indeed appear to offer a whole new era of four-stroke performance. Even though Campbell never got a clear lap during Le Mans qualifying, he put the NR second on the grid, just behind Dominique Sarron’s RVF. In the race he got a great start and completed the first hour just behind the Frenchman.

But when the Aussie went out for his second stint, after Roy and Nemoto had ridden their first outings, he knew something wasn’t right. “I came back into the pits because the bike was starting to drag the rear wheel into turns. I told the guys it either had an oil leak or was most probably doing a big end. For some peculiar reason they put in a new tyre and told me to get going, but the engine failed before I’d even got out of pit lane.”

The much-hyped machine was out: swarf had blocked an oil gallery, leading to an engine seizure. It was another huge embarrassment for Honda, especially for project leader Takeo Fukui who had also led the NR500 project. Fukui was an important man and his involvement underlined the significance of the NR project – later he would become president of the entire Honda Motor Company.

“Le Mans was a huge disappointment for Mr Fukui and the rest of the Japanese, especially since everything had gone so well in testing,” adds Campbell. “It was such a huge project and it had been Honda’s dream for many years. They’d tried the NR in all forms and finally they’d come up with the goods, only to be stopped by a bit of swarf.

“According to the miles we’d done in testing the engine was more than capable of doing 24 hours and we would definitely have finished on the podium, barring crashes or whatever. But these things happen…”

16,000rpm, 170bhp

The NR was returned to Japan and everything went quiet again. Then later in the year HRC announced that they would contest Australia’s prestigious Swann Series, with Campbell and team-mate Robbie Scolyer aboard a pair of NRs.

“This time the bikes were going to 16,500, which was a lot of revs in those days,” says Campbell. “And they were making about 170 horse, when the maximum any of the 1000s was making was 145 tops.”

Campbell might have won the Swann if he hadn’t messed up in the first race at Oran Park. “I clipped a ripple strip and put the bike down. I felt pretty guilty about that one.”

HRC suspected that Campbell’s NR had ingested some dirt in the accident so mechanics removed the engine and flew it back to Tokyo, as hand luggage! “They took it back to Japan first thing Monday, rebuilt it and brought it back for first practice at Calder Park on Thursday. They don’t do things like that today – it was serious stuff!”

![]()

Campbell won a race at Calder and got a couple of podiums the following weekend at Lakeside, but the Swann title went to an up-and-coming youngster called Kevin Magee riding a factory-powered Yamaha FZR1000. Once again the NR was returned to Japan and once again it all went quiet. And this time it stayed like that, at least for five years before Honda launched the next phase of its oval-piston adventure: the NR750 road bike, a rolling showcase of Honda technology that retailed at £38,000, five times more than a Fireblade. The company was still determined to prove that the NR500 hadn’t been a hugely expensive waste of time.

Lost legacy

The NR road engine was based closely on the racer and had a similarly huge spread of power – 70 per cent of torque available from 7000rpm to the 15,000 red line. The bike was certainly cutting edge, with Honda claiming more than 200 patents, including 50 for the piston rings alone. Getting oval rings to seal properly within the oval bores had always been the biggest challenge throughout the NR project.

Then came the revelation: the real reason for the existence of the NR750 race bike. During the road bike launch Honda announced that the 750 was in fact the first of a whole range of oval-piston street bikes. Next up in the NR programme were a mega-torque large-capacity touring bike and a long-stroke v-twin sports bike, while persistent rumours suggested a single-cylinder on/off-roader would also be on the way. Technophiles the world over licked their lips and waited.

![]()

But not one these machines ever made it into production. For once, the world’s biggest motorcycle manufacturer had overstretched itself, its ambition getting ahead of its capabilities. Manufacturing costs of oval-piston engines were prohibitively high and Honda were coming under increasing pressure from rival manufacturers who feared that a technology race might bankrupt the industry. For the same reason oval pistons were banned from just about every type of racing going and it’s still that way today – they aren’t allowed in World Superbike or endurance or in any MotoGP class.

Honda’s radical blue-sky thinking might have made sense in the soaraway 1980s when the world was awash with cash, but the Japanese economic crash of the early 1990s changed everything for the motorcycle industry.

“The 1980s were an unbelievable era,” agrees Campbell. “The factories had money to spend and there was good money to be made wherever you were racing. It’s very different to the way it is now.”

The world has indeed kept on changing. Instead of creating 15,000rpm oval-piston flights of fancy, Honda has spent a long time forging a new way with bikes like the NC700X, a clever, common-sense machine created for a poorer, more pessimistic world. It would be a generation before the advent of the RC213V-S.