750/900SS Restorations

Cheaper than many Dukes, the Super Sport makes an easy and affordable resto. Just ask this lot…

![]() ucati’s 750 and 900SS of the 1990s are great reflections of the firm’s ethos, blending power, handling and light weight with clever yet classic engineering. The sort you can soon get your head and your spanners around. Their genius has been subsumed somewhat by the 916 and 748 and, to a lesser extent, the Monster series. It’s a shame because while the desirability of those continues to grow, the Super Sports have languished largely forgotten.

ucati’s 750 and 900SS of the 1990s are great reflections of the firm’s ethos, blending power, handling and light weight with clever yet classic engineering. The sort you can soon get your head and your spanners around. Their genius has been subsumed somewhat by the 916 and 748 and, to a lesser extent, the Monster series. It’s a shame because while the desirability of those continues to grow, the Super Sports have languished largely forgotten.

In 1989, Ducati engineering supremo Massimo Bordi set up separate production lines. One would pump out the liquid-cooled, four-valve, fuel-injected 851 range and the other would concentrate on the air-cooled, two-valve, carburated twins. He knew the importance of the two-valve bikes and the affection they were held in by the more traditional enthusiast.

The first belt-driven camshaft 900SS of 1989 was an imperfect precursor to the machine launched at Cologne in September 1990, and the single Weber-carbed edition is one you still want to avoid. The second incarnation used a pair of 38mm Mikuni CV carbs but its genius went further. The frame had less rake and trail to quicken steering, augmented by a new aluminium swingarm to shorten the wheelbase, attached to a Showa shock that lifted the rear. Showa also suspended the front with fully adjustable usd forks, while larger 320mm Brembo discs graced the front end. The bike was offered in faired and half-faired versions.

Using what Bordi designated the ‘small crankcase’ of the Pantah, the 750SS only had five gears to the 900’s six. Yet the benefit of the 750 and 900 being less celebrated than Ducati’s other ’90s legends means they are a far cheaper way into ownership of Bologna’s best. They’re also easier to work on than the liquid-cooled sportsbikes.

Ducatis of all eras suffer from reputations for mechanical complexity. Yes, they might be different in many ways but these four owners have seen beyond that to revive these examples. Set your prejudices aside: Ducati restoration and ownership may be easier and closer than you think.

![]()

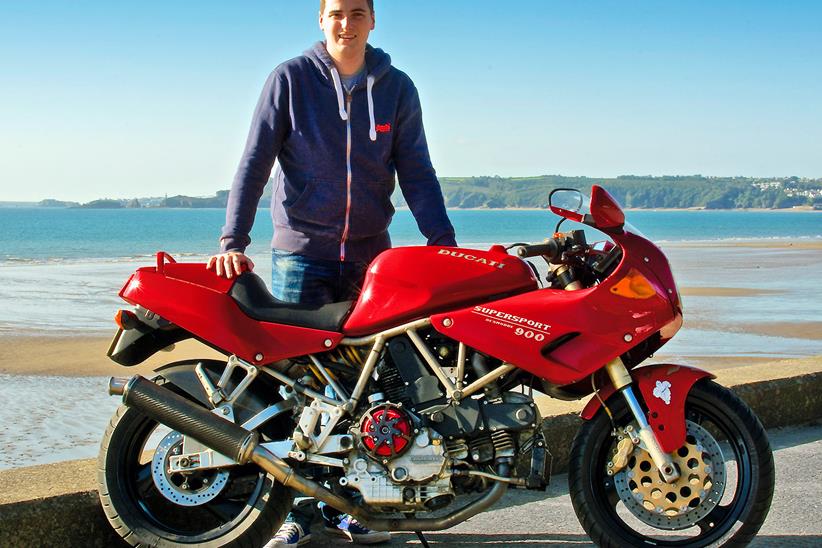

1992 900SS

James Adams, Whitland, South Wales

“I was looking for a Ducati 900SS and a friend of mine happened to know of one that was going. It’d been owned by this guy who was in the army and was obviously off here and there, so the bike had been left at the bottom of his garden for three years.

“It was in quite a state. He’d put a cover over it but that had blown off and it was actually lying on the grass because it’d been knocked over by the wind. All the panels were knackered. I ended up giving him £500 for it.

“I got it home, put some petrol in it, fitted a battery pack and managed to get it running – but it sounded really rough. I changed the cambelts, which was fine, but when I went to change the oil I had a three-litre tray underneath to catch it and the oil spilled over the sides. In the end there were five-and-a-half litres of oil in there – it transpires that it’d had a leak but the owner had just kept filling it up. That explained why it was really hard to start. After fixing that, along with the fitting of a new clutch mastercylinder hose and a new fuel filter, it was a completely different bike.

“The full fairings that came with it were in terrible condition, but I ended up getting really lucky on eBay with some half-fairings. They’re original, but there doesn’t seem to be an awful lot of aftermarket stuff around for the 900SS. Other than eBay I’ve got quite a lot of parts from Moto Rapido, plus a website called stein-dinse.biz which does loads of NOS stuff quite cheap. American eBay is a good source of parts too, especially seeing as the 900CR was specific to the US market but the parts are exactly the same as the 900SS’s anyway. The half-fairing has a special bracket that holds it on which I couldn’t find in Europe, so that came from the States. There’s also a tiny little tap underneath the tank that was tricky to find – I got one in the end, but it cost me £30.

“Even so, the 900SS is a pretty cheap and easy bike to restore and is a really good introduction to Ducatis. I’ve done about 1000 miles on it since I finished it – I love it.”

![]()

1992 900SS

Nick Anglada, Orlando, Florida

“This 900SS was an ex-track bike when I got hold of it – it had these headlights that were zip-tied to it and a homemade paint job that looked like it had been brush-painted onto the upper fairing. It wasn’t pretty.

“I knew I was going to take the bike apart so the first thing I did was take the engine out and cylinder heads off – with the humidity we have here in Florida, you get condensation inside the cylinders a lot.

“Next, I sorted through every single nut and bolt. For the right finish I took the zinc-plated bolts and put them in a bucket of water with some laundry detergent overnight. When they come out they’ll still have that yellow finish, but it’s flat not glossy. I learnt that from off a friend who restores Ferraris.

“A lot of people don’t know that the top triple clamps are actually painted on these early 900SSs – if you strip the clear coat with paint stripper, wash it, dry it and clear-coat it again, it goes back to the original finish.

“Getting a 1991 900SS is almost impossible in the US, but there are a few ’92s like this out there. Once you’ve got your hands on one, it’s one of the easiest bikes around to restore. Lots of service parts are still available – it’s not like you’re trying to restore a 1981 Pantah. That said, some things can be tricky: the early models had gold forks which can take a while to hunt down, and the ’91 and ’92 models had a shorter crank – originals of that can be difficult to find.

“From 1994 the 900SS got things like carbon fibre front and rear mudguards and an underslung brake assembly – it’s parts like this that make restoring a ’94-’97 SS more expensive than a ’92 like this.

I supply a lot of used parts on nickangladaoriginals.com, although getting original bodywork is a challenge.

“As much as you want to keep it original the 900SS has the ‘suicide’ kickstand – every time you move the bike the kickstand automatically retracts. You either have to address it or get used to it, as I’ve seen a lot of bikes fall over because of it.”

![]()

1996 900SS

Chris Bunce, Fleet, Hampshire

“I bought this 900SS for £2000 two years ago from a dealer on eBay. I went round the Ducati factory in 2006 and have been going through a Duke phase ever since: I’ve had 748s, 999s and a 916SPS, but I wanted something cheaper that still looked great. The underrated 900SS fitted the bill.

“It looked lovely, although a friend of mine had warned me, ‘Just be careful – check the sprag clutch and look for a cracked frame up by the headstock.’ I gave it a glance and it all looked fine, but when I gave it a basic service and tidy I noticed the frame was indeed cracked – a common problem with these bikes. The funny thing was that I wasn’t planning to doing a full resto on it, but once I saw this I knew I had to.

“I got everything off the frame and took the engine out. The engines are painted silver and that paint deteriorates badly – that needed refinishing. While that was out I re-did the valves, bearings, oil seals – it was quite a big job, but it’s an easy engine to work on.

“It’s hard to get certain parts for the 900SS, but for basic engine spares it’s excellent. You have to remember that this bike has been around for years and the parts have been used in pretty much everything. That said, try getting hold of the little bracket that holds the tank clips on the front. Impossible.

“Even so, it’s a great bike to restore. People can be scared of doing Ducatis but I’ve no idea why. Find a 900SS that’s as unmolested as possible, and has been stored somwhere dry – classicsuperbikes.co.uk is a good place to look. Generally with Ducatis, if they’ve been stored badly and extensively modified then you’ve got a lot of work ahead of you.”

![]()

1991 750SS

Paul Mead, Stowmarket, Suffolk

“I always wanted to restore a 750SS – I’d only owned 250s before so I didn’t really feel like I needed the power of the 900. I got this one six years ago as a wedding present from my wife.

“It wasn’t in too bad a state when I went to pick it up: the front fairing on the offside was smashed, the indicators were intact although the actual bearing was broken, the exhaust was scratched and the rear indicator was hanging off – pretty good for £900. It was a prime candidate for a resto job.

“The first thing I did was strip the carbs off and clean them out, as the bike had been standing in a garage for eight years. They weren’t too bad, so all I had to do was replace the carb body on one of them. It had a Stage 1 dyno chip kit in when I got it but I had no end of problems with it idling, and a Stage 2 kit didn’t solve that problem either. It turned out that there was an O-ring missing, letting air in. It was an easy fix and I’ve never had any more engine problems.

“It’s the bodywork that will cause you problems when restoring a 750 or 900SS. Those bikini fairings are hideous to find, and if you do manage it they’re very pricey.

I repaired my broken fairing by fibreglassing the cracks, and then painting that and the other one to match. The thing I really struggled with was finding that little sticker that says ‘Desmo’. I ended up getting it from somewhere in Germany – it’s for a 750 Paso, but it’s the same sticker as the one on the 750SS.

“It used to be easy getting stuff on eBay, but things are going crazy on there now. I saw a 900 seat that went for a quid a few months ago, but it’s getting harder to find those kind of serious bargains. I think the SSs have just hit that point where they’re really starting to increase in price a bit.

“My 750 is one of the dry clutch ones, so it’s the same engine as the 750 Paso. The clutch side of it is very hard to get parts for – they hardly ever come up. The clutch cover is like gold dust. You’ll easily shell out £200 for a secondhand one of those with no idea whether it’s any good or not.

“One of the biggest challenges of an older 750SS like mine is the Allen head bolts. Be prepared to drill them out, because the heads get seized into the aluminium cases. But the hardest thing is the carbs – I don’t mean restoring them, I mean getting them on and off and setting them up. The balancing screw is buried quite a way up there – you need a foot-long screwdriver to get to it, and be prepared to burn your nose on the exhaust as you’re trying to find the head of the screw.

“But don’t be scared of a Ducati, and don’t believe what some people say about them.

I haven’t had any electrical problems, and it always starts when it’s wet. I wouldn’t get rid of my 750SS now. In actual fact, I’m currently looking for a 900SS to restore as well…”

Words: Alan Seeley & Hans Seeberg