Move over Colin, it’s my turn now

THE rider in front disappears from view. I lean the bike into the chicane before the start-finish straight, feeling the racing wets digging in.

The bike boots it out of the first-gear corner, lifting its wheel as I gun the motor. It booms into second via the slick quickshifter, the revs dropping slightly before the power builds again.

The acceleration rushes in. It rushes in hard. Hard enough to lift the front wheel as it snicks into third. I put my weight over the front and get my head tucked down behind the screen.

Fourth chimes in as fast as you like and my damp visor steams up as I hook fifth. It’s right about now that my jet-lagged brain realises that just where I’ve hooked fifth gear is where I braked last lap.

My eyeballs do a good impression of leaving my head as my brain clicks into overdrive to take in my surroundings. At around 140mph the pit wall is rushing past and the gravel trap is approaching way too fast.

I have two options. Gravel trap or corner. Within a split second, as the handlebars waggle wildly and the phenomenal brakes do their best to scrub off 80mph, I make my choice.

Yes, this very special SP-1 is worth around half as much as the woman Chris Tarrant handed a very fat cheque to last week. But to try and pitch it into the corner would mean an almost definite interface between fairing and Tarmac.

I opt for the gravel, sticking to the left-hand side, and hit it at around 80mph while still braking as hard as I dare. I grip on tight as the bike snakes its way through the deep chippings with the end of the trap in sight. There are a few feet to go. Brake, brake, brake. The bike stops just in time, my foot comes down to support it and I catch my breath. That was, er, exciting,

With the bike in one piece and myself thankfully unscathed, I chug the twin back out of the gravel. I slowly do another lap and bring it back to the pits. As I pull in, one of the most senior men in bike racing hugs me for not crashing. Phew.

It was a close one. But what I’m really worried about is how my near-miss will go down with the men from HRC. Because as well as the bike I’ve just ridden, they’ve agreed to let me sample three of the most desirable motorcycles in the world, including two GP bikes and one that won the WSB championship in the hands of Colin Edwards…

And I’m concerned that they may be having a sudden change of heart. For all I know they could be pencilling the name ” Potter ” into a big black book under the heading ” Don’t let this man ride any more of our bikes. Ever ” .

Just a few hours beforehand, I had opened the curtains at the Twin Ring Motegi hotel and drunk in the panoramic view of the twisting Japanese circuit surrounded by jagged mountains. A misty, wet race track with rain slashing across it was not what I wanted to see three hours before I was supposed to be on a circuit I had never ridden in my life.

I was nervous, my brainwas still befuddled by transcontinental travel and my eyes were bleary. But even so, the adrenalin was coursing through my veins at the prospect ahead of me.

However, it was only after I had wandered open-jawed around the amazing Honda Collection Hall museum that I started to take in just what I was about to embark on.

I’ve come here for the extremely rare chance to ride what are probably the most special race bikes in the world. The kind of bikes that crop up when you’re really drunk and the conversation starts getting into ” if I had a million pounds ” territory. Then the beer monster takes you home and it’s forgotten about until you watch the next GP or WSB race.

And the track? The track is a mystical place you’ve dreamt of riding at since you saw technicians milling around laying the Tarmac four years ago. Well, I had anyway.

After a traditional Japanese breakfast of bacon and eggs (Brits on tour, eh?), I join the entourage of 14 journalists from around the world at the pit lane garages of Japan’s newest and biggest race track, filled with HRC trucks.

We’re handed HRC umbrellas to cross the Tarmac, marched into a garage and shown the coffee machine. I’m too fired up for caffeine, though. I stick my head out into the rain and sneak down to the next garage. The mile-high grandstand looms over the pit lane, with the small dots of spectators at the top.

And lined up in front of me is one of the sexiest sights I’ve ever seen – stag weekends in Amsterdam included. There’s Alex Criville’s V4 NSR500, the SP-1W that carried Edwards to the WSB No1 plate this year, Daijiro Katoh’s NSR250 which finished third in the world championship, and the Team Cabin SP-1W that took Katoh and Tohru Ukawa across the finish line first in the prestigious Suzuka Eight-Hour endurance race.

A cool £5 million is a rough estimate of their total worth. But it’s not about the money. Riding any of these machines is the dream of anyone who loves bikes and has ever been near a race track.

But that’s just what we’re going to do. Fourteen journalists, a couple of laps on ” ordinary ” bikes to familiarise ourselves with the track, then four laps on each race bike.

We’re handed a schedule for the day. The Team Cabin Suzuka Eight-Hour bike is my first mount. It’s basically the same as Edwards’ WSB SP-1, but it features a different swingarm for fast wheel changes, revs 500rpm lower to a mere 11,750rpm, wears Brembo brakes instead of Nissins and has a slightly softer suspension set-up.

With the first riders ready to go, HRC president Yasuo Ikenoya talks us through the day. There’s a nervous tension in the air. The riders are nervous due to what they’re about to get their legs over and the Japanese are nervous because they’ve never done anything quite like this before.

And it looks like they have every reason to be as I return to the pit lane after my gravel trap adventure. But luckily for me and my image – it’s never pleasant to see a grown man cry – HRC are happy to let me carry on riding. And next up is Katoh’s NSR250.

The nearest I’d got to riding a two-stroke 250 was a few club races on an MZ250, a race on an RD250LC and a bit of track riding on an Aprilia RS250 – not bikes that prepare you for a 250cc

V-twin that makes more than 90bhp and weighs 96kg (211lb). That’s a power-to-weight ratio that gets close to shaming an F1 car!

As I walk down the pit lane, the tiny two-stroke is being warmed up, rasping and zinging as the throttle is blipped. The chief mechanic hands me the bike and I lower myself on to it, feeling as if I’m sat on the back wheel. It’s so small – but then I am 6ft 4in tall.

I slip the clutch and kangaroo my way out of pit lane. Blaarp, bleurgh, blaarp, bleugh. Eventually I let the clutch out and it drives its way through the bogging down period as the two-stroke smell wafts into my helmet vents.

It has stopped raining, but the track is still sopping wet. The 250 instantly feels good, though – like a proper race bike. It’s so small and light, it feels as if you’re riding on fresh air. Think and it turns. Blink and it stops. You barely have to concentrate on the chassis at all. It does everything without effort and sweeps through corners holding the tightest of lines, the tyres sending so much feedback to your brain it’s incredibly easy to get on with.

OK, so the motor needs a bit more concentration to keep it on the pipe, but it drives surprisingly well from 8000rpm, whipping up to 12,500rpm with a crisp, clean and invigorating rasp that sounds even louder than the 500 when it comes past the pit wall.

But perhaps the best part of riding a 250 GP bike is coming into corners. There’s basically no engine braking at all. Back off the throttle and everything goes quiet. Then gasp in awe as the blaring two-stroke gets blipped and the only other sound you can hear is the zing of the calipers pushing the pads on to the discs.

With four laps done, I pull in, bow again – this is Japan, after all – and hand the bike over. And I’m absolutely buzzing. Although the bike is as quick as, say, a FireBlade, it’s just so easy to ride and much less stress than the previous SP-1 – with or without the small detour.

With some anti-jetlag coffee consumed, I try to settle my stomach with some Japanese offerings in one of the many eateries at the Twin Ring Motegi complex. But it’s hard to settle anything when you’re about to ride the most awesome race bike ever invented. A bike that has won more races than any other and is renowned for taking no prisoners.

The previous night, I’d spoken to the snappily named Honda Large Project Leader of the NSR500, Shigeru Hattori, about riding his baby. He said: ” Riding the NSR500 is very easy if you ride in the middle of the power, but it’s not so easy for anyone to ride at the top. ”

I ask him if he’s ridden one. ” Yes, but only in the middle, ” is the reply.

I get ya. So, just to check. An estimated 190bhp and 131kg (288lb). And this one with the more savage screamer engine instead of the calmer big bang motor of previous years. I’m told the power curves of the two motors are identical, but the latter one spins up the revs quicker. There’s also no quickshift – apparently the gearboxes are too delicate to cope with one.

Lid on, leathers strapped up and gloves sealed, I spy the mechanic for Criville’s NSR500 standing with the bike’s front wheel between his legs, waiting. I take in a sharp intake of breath and walk towards it, noticing the full wet tyres and the four gorgeous titanium pipes exiting from the seat unit and side of the bike.

He takes the tyre warmers off and my destiny beckons. I get a push-start from the mechanic and dump the clutch. The bike crackles into life, I pull the clutch back in and blip the throttle twice. It responds to my right hand so quickly it scares me. Literally.

I exit on to the wet, black Motegi Tarmac. At low revs the NSR500 pulls like a road bike. The four pipes are burbling as I edge into the first corner. It’s much bigger than I thought – though still way smaller than something like an R1 – but it feels oh so light.

On part throttle in first gear the bike just wants to go. As I ease open the throttle it’s hunting and crackling, just begging me to unleash it. It won’t have to wait long.

I tweak the throttle open just a fraction. It’s as if it’s connected directly to the rear tyre. Every movement of my hand dials in exactly what I ask. I mean exactly.

I’ve never seen a rev counter climb so quickly and before I know it I’m through third and fourth gear and laughing out loud.

It takes about a second between gears before the rev counter is back at 12,000rpm. Baarp, baarp, baarp, baarp. My body’s pushed over the top of the tank and my weight’s right over the front wheel. The bike lifts off every time I change gear and barely has time to touch down before it’s back in the air again. And, boy, is that noise horny. Believe me, riding a 500cc V4 two-stroke on full chat underneath you makes you scream and laugh inside your helmet.

I’m on the first straight and using both sides of it as I fight the gargling beast from side to side. At the 150 marker I’m on the brakes, changing down through the reverse-shift box and remembering there’s no engine braking. The Brembos take a good squeeze to get them to bite hard. It’s how Criville likes it, but they don’t suit me.

I’m into second gear for the left-hander and on part throttle, building the revs delicately as the second part of the corner opens out and I pile on the revs. By the time I’m at the exit kerb with my wheels running inches from the wet blue and white stones, the bike’s doing a full-on wheelie. I back off, shift into fourth gear and it does the whole thing again.

I hang on to fourth gear with the front wheel finally coming down and get on the brakes again for the next right-hander. As soon as it’s in the corner I’m on the gas and the rear wheel attempts to leave itself a foot wide of the front as I hit some standing water.

I increase the revs tentatively as the sound of the wailing V4 echoes through the underground tunnel. Then it’s up to fourth while still cranked over, using the mid-range, as the next sweeper opens out. A bit more throttle and the front wheel’s hovering again before I’m back to second and whip it through the chicane.

It turns like you wouldn’t believe and does everything you’ve always wanted a bike to – short of turning into Melinda Messenger after a rideout. After the sweeping chicane there’s another short straight and a wet hairpin. I spy a camera crew on the inside of the bend. My knee touches down on the wet tarmac and it feels totally safe. You could stand up and jump around on this thing when it’s cranked over and it wouldn’t flinch. I would, though, especially with the thought of a £1.5 million bike underneath me.

Out of the hairpin, I’m easy on the throttle as the longest straight opens out and the bike puts itself precisely where I point it. I race through the box down the straight, fighting every gearchange and carefully dialling in the revs as it goes all bucking bronco on me. At 9500rpm in sixth gear (around 170mph), I bottle it, hide behind the screen and feel my leathers pulling my shoulders around in the wind.

On the brakes again, the bike crackles as I blip down the box to turn in before delicately dialling in a bit of throttle to pick it up. Clouds of two stroke billow as I pass under the next bridge. I scythe through standing water and line up the next chicane for another lap from the gods.

Afterwards, I’m a different, quieter, shocked person. I’ve only done four laps and the weather has been about the same as back in the UK, but I just can’t stop sweating. It has totally blown my mind. Few things live up to your expectations. But this has been everything I was expecting and 10 times more. Savage just doesn’t even begin to describe the experience. If you get the chance, take it – but expect any bike you ever ride again to disappoint you.

After half an hour of silent contemplation of what I’d just been through and thoughts of how the hell 500 GP racers ride these things flat-out for 23 laps, let alone sideways at 100mph, I wake myself up and walk towards Edwards’ Castrol Honda SP-1W.

The bike’s in the garage on its paddock stand, the Michelin wets clad in tyre warmers. I’m shown around the bike and adjust the brake and clutch reach to suit my hands. The tyre warmers are taken off and I get on. I thumb the starter button, fitted for convenience so if a rider crashes he can still carry on, and the massive 70mm titanium pipes and carbon Akrapovic silencers shatter the peace of the pit garage.

After the alien experience of the 500 it instantly feels more familiar and memories of my own SP-1 come flooding back to me.

The bars are lower and narrower and the pegs are high and stubby, but the riding position is similar and it still feels like, and sounds like, an SP-1.

The engine whirrs, the pipes boom and a claimed 180bhp comes into play. It feels heavier and bigger than the 500 but, God, does it accelerate. The mid-range isn’t as strong as Neil Hodgson’s INS Ducati that Edwards has seen so much of in British WSB races this year. But the top end blows it into the weeds. From 8500rpm the bike bellows its anger from the pipes as it speeds towards the horizon.

On the way into a corner the Nissin brakes are a touch sensitive and unbelievably sharp. But, unlike a road bike, the suspension doesn’t dive under heavy braking. It just slowly dips as the front tyre takes the load. It turns in sharper than the Suzuka Eight-Hour bike, but a touch behind the 500.

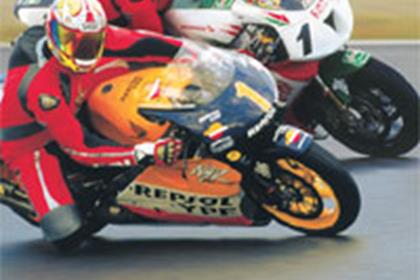

I come out of the chicane round the back of the circuit and hoof it down the short straight towards the hairpin, riding the revs and feeling the kick as the quickshifter snicks in another gear at 13,000rpm and the green shift light flashes. I glimpse an orange and blue bike on the brakes on the way in and set my sights to lock.

I’m riding the number one WSB machine from this year. In front of me is the NSR500 that’s carried the number one plate all year. This is a special moment. As the SP-1 guns its way up through the gearbox it wheelies in first, second and third before settling down at 10,000rpm in sixth. Even going as fast as I dare, the bike is less stable than the NSR500, but there’s not much in it. I watch as the NSR500 peels into the next right-hander. I bang the shifter down the box, conscious of the race shift. I try not to get too carried away, peel in, scrape my knee in the wet again, then burn my boot on the exhaust. I ignore the smell and reel him in.

I sit on him through the chicane. It seems like he’s having an easier time with it than me, probably a lot to do with the extra 30kg (66lb) my bike is carrying.

I see him get on the throttle and I inhale the blue smoke from the four pipes. I’m on the gas around the same time, picking the bike up and feeling for the wet tyre. Halfway along the straight, my head’s down behind the screen and I start to move out to the right. He’s not getting away now.

As he sits up I’m alongside him. I’m a bit late on the brakes into the first turn and lean the world’s fastest SP-1W in. I drift out, the bike obeying my every command, and leave him in a four-stroke boom up the next straight. My first taste of what GPs will be like when they allow four-strokes to run with two-strokes perhaps?

But though I managed to overtake the 500 and it wasn’t much quicker than the SP-1, it’s the way it feels that makes all the difference. The SP-1 is fairly easy to ride – as easy to ride as a 180bhp

V-twin could be. It just continues to pile on the revs in one smooth curve. The 500, on the other hand, is like a living thing, which means it takes so much more out of you.

Around Motegi with Edwards on board, the Castrol Honda is just one second slower than the NSR500. At some tracks the WSB bikes lap faster. But as 2000 500 GP runner-up Valentino Rossi said after he rode a Castrol Honda at the Suzuka Eight-Hour: ” You can ride superbikes at 100 per cent, 99 per cent of the time, but you can only ride 500s at 100 per cent, one per cent of the time. ”

Well, maybe you can, mate…

REPSOL HONDA NSR500

Specification

Engine: Liquid-cooled, 499cc (54mm x 54mm) two-stroke reed valve V4.

4 x Keihin carbs. 6 gears

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar

Front suspension: Showa forks, adjustments for pre-load, compression and rebound damping

Rear suspension: Showa single shock, adjustments for pre-load, compression and rebound damping

Tyres: Michelin slicks/wets

Brakes: Brembo; 2 x 320mm front discs with 4-piston calipers, 220mm rear disc with 2-piston caliper

CASTROL HONDA SP-1

Specification

Engine: Liquid-cooled, 999cc (100 x 63.6mm) 90°V-twin, four valves per cylinder. Fuel injection

Chassis: Aluminium twin-spar

Front suspension: Showa forks, adjustments for pre-load, compression and rebound damping

Rear suspension: Showa single shock, adjustments for pre-load, compression and rebound damping

Tyres: Michelin slicks; 120/70 x 17 front, 190/50 x 17 rear

Brakes: Nissin; 2 x 320mm front discs with 4-piston calipers, 220mm rear disc with single-piston caliper