MTB to motorbike: The Mod 1 test

Given how everyone I know with a motorbike says the first practical test is harder than the second, I was surprised to discover it usually takes about 15 minutes and mostly involves riding around cones in a car park. Like a CBT for grown-ups.

However, just like the advice my grandad gave me before school exams (‘they’re easy if you know all the answers’) the Mod 1 test is only simple if you can complete the series of tasks precisely and within certain strict parameters – minimum speeds, observations before moving away, stopping in a certain area, that sort of thing. This is where it gets complicated.

Particularly when you mix in my own false confidence brought on by a few blissful months of good weather and almost daily rides on the CB125R Honda had leant me, where I’d spent my time getting my head around counter steering and body positioning on my favourite local B-road. And crucially, not doing any U-turns.

I’d done loads of low speed stuff at first, at least 20 minutes at the start of every ride. For me it was the same as pedalling my mountain bike uphill in order to enjoy the ride back down again; not as much fun as the ride itself but a necessary evil. But then I’d got overconfident and decided my time was better spent razzing around country lanes.

So, I was in for a rude awakening the morning of my Mod 1 training where, sat astride a much larger (and comfier) Honda CB650F, I discovered I could no longer gracefully weave between a set of cones. Plus, I was putting my foot down on almost every U-turn, and half of the figure eight attempts.

![]()

Let’s get excuses out of the way – I’d been told (by people on YouTube) that I’d find a larger bike easier to manoeuvre at low speed because it had a lower centre of gravity. Maybe it’s just me, but nothing could be further from the truth. Where the 125 could be leant and snapped back upright with a twist of the throttle, I found the bigger bike’s weighting inconsistent (at a certain angle it would just drop like a wheelbarrow) and slower to react to the gas.

The U-turn was the big problem. With every attempt I was finding it harder to complete the manoeuvre without planting a foot, not helped by the fact my training partner seemed to be nailing every one.

This went on for 20 minutes or so before my instructor Dougie identified a spiralling crisis of confidence. ‘I can see it on your face, you’ve decided you can’t do it before you’ve even set off,’ he said, before making me ride a circle around him until I was dizzy. The point of this being to make me focus harder on the spot I wanted to ride to, and to stop my attention wandering to a pile of leaves or crack in the tarmac I was trying to avoid.

Also, I was leaning the wrong way. Now – those of you who have read my earlier updates will know this is a long-standing issue, because cornering on a mountain bike requires you to lean towards the outside of the corner, instead of into it like you do on a motorbike. However, it’s also the reason I found the car park stuff on the CBT so easy, because at low speed you want to lean out to counteract the bike’s desire to fall over.

However, I’ve spent ages deprogramming my natural instinct to lean out on a motorbike, and was consequently making the thing unstable at low speed. Basically, it seems whichever way I lean, it’s wrong.

Still not feeling particularly confident, we moved on to the higher speed exercises – a controlled stop within a box, an emergency stop, and a swerve to avoid a hazard. Thankfully here I was reasonably competent, particularly with the swerve as it employed the counter steering technique (push left bar to go left) I’d been practising in my own time.

![]()

As a breather from the car park exercises (for riders and clutches) we went out for a road ride in the afternoon, my first real experience on a bigger bike. This did my confidence no end of good – mainly because Dougie was quite complimentary about my road riding – other than occasionally using one or two fingers on the front brake at low speed. Look, it’s the way I’ve done it on a mountain bike for the last decade, so cut me some slack. Why do motorbikes need such massive brake levers anyway?

Feeling decidedly looser I attacked the cones with assurance and found the slalom much easier. Adding a couple of mph to the figure of eight meant wider circles but much better balance. More speed is always the answer.

Hoping to bring this success to the U-turn, my fellow learner revealed his secret – using a bit more gas to pull away so you can get most of the turn done early while the bike is stable, that way you’re not trying to turn in while naturally slowing down. Dougie agreed, ‘commit to it early and get it done,’ he said, rather than leaving all the turn to the second half of the manoeuvre.

That lead to the ridiculous sight (and probably sound) of me pulling away, turning my head as far to the right as it would go and shouting ‘COMMIT. COMMIT. COMMIT’ to the inside of my helmet. It worked! I got around and with about a foot to spare, rather than a foot on the ground, so I decided I didn’t care how daft it was.

A day off followed before test day, which necessitated a 5.30am alarm. Except my toddler woke up at 3.30am, and I’d struggled to get to sleep with test day nerves, so it’s safe to say I set off feeling less than rested.

Due to coronavirus complications the other learner rider and I would be taking our Mod 1s in separate locations. The first was an hour’s ride from the school in Milton Keynes, the second (mine) an hour from there, and then another hour or so’s ride back to the school.

I was secretly grateful to be going second – if I was first and failed I’d have to do all that riding afterwards in a bad mood and potentially cast a negative shadow on the other rider’s day. Plus, as the training day proved, I’d got more confident with the low speed stuff the longer I spent riding normally on the road. So, my fingers were crossed, although not while riding obviously.

We had a brief warm-up around the cones and then set off. I made sure to end on a high – a nailed U-turn – but before becoming complacent with the whole thing. The ride to the test centre involved some towns and dual carriageways and I can’t tell you how good it feels to accelerate to the national speed limit without having to duck between the dials like on the 125.

At the test centre my riding colleague had a bit of a wait before being allowed to take his test, which he passed with barely a minor. We then watched another rider set off from the car park, completing his shoulder checks but failing to indicate when turning at a marked junction that lead to the test area. The examiner looked down and noted this on his clipboard. Let this be a lesson – the entire Mod 1 is conducted in road conditions from the moment you get on the bike to the moment you get off, and the examiner is watching you the whole time. So do your mirror shoulder checks and pay attention to road markings.

After another hour or so on the road (plus a trip to what was apparently Cambridge’s best coffee shop) we arrived at my test centre. The parking area was about ten metres from the Mod 1 area with no junctions to consider, which was a relief.

I parked nose out at the end of the parking area to make the turn into the fenced-off test area easy as helpfully advised by my instructor and went to have a look at the layout. I’d been hoping the flatter topography of the test centre’s billiard table-smooth surface would tip the scales in my favour, with no piles of leaves like where I’d practised. It was also massive, at least three times the size of the car park I trained in and set up for a left-hand turn like I’d been practising.

The time for the test came so I took a few deep breaths and went through the start-up routine I’d practised dozens of times, did my mirror shoulder checks, and pulled away without stalling into the test area. So far so good.

![]()

What does the Mod 1 involve?

First up you park in a box marked by cones nose-in, and then have to push it out backwards in a semi-circle into another box marked by cones, while doing observations and not dropping the thing on the floor. Or leaving the stand down. Or discovering you’ve left it in gear. Or running your own foot over.

Then with it facing forwards, you get back on, do your mirror shoulder checks and slalom between a line of cones, focusing on the one closest to you in order to maximise the space between them for your turn. At the end of the line you do a couple of figure eights (I still can’t work out how many you’re supposed to do) until the examiner calls you over. This all went fine and served as a good warm up for my tense shoulders and neck.

Next up is the low speed ride – there are no points for doing this at 1mph, it’s not a motorcycle trials event – where the examiner walks beside you. Try not to run over their foot as this is almost certainly a fail.

This brings you to the U-turn arena, which if you’re anything like me, will be the section that your Mod 1 success hinges upon. The box where you start the manoeuvre is about a foot over from the left-hand line of cones so you’re already at a disadvantage, so after setting off you drift left over to the line, do a mirror shoulder check, and then turn your head and the bike to perform a perfect 180 (while yelling COMMIT to yourself) before coming to a stop.

I still can’t actually believe I managed to complete the move without sabotaging myself with nerves or a panicky throttle roll-off. I think it was actually the best U-turn I’ve ever done, and I had to take a moment to not then get carried away and mess the rest up by setting off over-exuberantly and doing a wheelie. I’m not certain, but I reckon this is a fail.

Hard bit over (or so I thought) the next exercise is arguably the easiest one – ride off, do a sweeping left hand turn between the cones with no prizes for getting your knee down, and then come to a controlled stop in a box. Or if you’re like me, stop ever so slightly shy of the box, before nudging the bike forward a bit. Did the examiner notice? His poker face revealed nothing.

The controlled stop is also a good chance to test your run-up for the emergency stop, which you have to complete at a minimum speed, something like 32mph, governed by a speed trap. There’s a lot more space to play with at the test centre and therefore a longer straight to nail the throttle, but it’s a good idea to get around the curve smoothly and start building speed from the corner exit.

I managed to avoid tripping the ABS or locking the rear wheel on my test and pulled up in one movement as opposed to grabbing the brakes on and off, but it felt like I took a lot longer to stop than when we’d be practising. I didn’t run the examiner over or anything, but I didn’t feel like I’d exactly nailed it.

Finally, there’s the avoidance test, conducted in the same coned-off area as the controlled and emergency stops, except you have to swerve around a cone left or right instead of stopping, and then wait in the box at the end. Here you can fail by going too slowly or by looking at the cone and hitting it. This is easier to do than you’d think.

Upon completing the manoeuvre, I stopped facing the fence at the bottom of the test area and waited for further instructions. None came. I waited a bit longer. Still nothing. Then I looked around and saw the look of disbelief on the examiner’s face as he was waving me back to the parking area, and had clearly been doing so for some time. What this does confirm though is that you do all the manoeuvres in your own time, so you don’t have to feel rushed. Take your time and settle down between each one.

Remembering the vital mirror shoulder checks (don’t do the whole test and then fail it at the last minute) I rode away and parked up to await my fate. By the time I’d got my helmet and gloves off the examiner was back in the test centre and was looking at his sheet while tallying something up on another piece of A4. He’s counting the minors, I thought, and is about to tell me exactly how spectacularly I’d failed.

Much to my surprise, however, he told me I’d passed. And with only one minor – turns out he had noticed me stopping short in the controlled stop and nudging my bike forwards. Argh!

Still, with that out of the way it meant we could have a bit of a blast back to Milton Keynes, taking in some great B-roads and fast dual carriageways full of roundabouts. I was knackered by the end of it, to be honest, after what had been a very long day.

Just Mod 2 to go now, where hopefully there won’t be any assessed U-turns, and then the real learning can begin.

MTB to motorbike: The theory test

First published on 14 October, 2020 by Adam Binnie

![]()

The next major milestone on my journey to unrestricted motorcycle access didn’t actually involve riding a bike at all, but did mean taking an exam for the first time in what must be at least a decade.

Still, the theory test should (in theory) have been one of the easier elements – and unlike the first time around, I wasn’t having to learn about road signs and who has right of way on a roundabout. Also during my 16 odd years of driving a car I’ve seen and learned to anticipate plenty of dangerous driving, so I reckoned the hazard perception would be reasonably simple too.

I remember one of my friends failing their theory test when we were teenagers and the ridicule was relentless. We still remind him of it to this day. I knew I could not afford (both psychologically and financially) to allow the same to happen to me.

Related articles on MCN

- How to pass your CBT and ride on L-plates

- How to ride a motorbike

- How to pass your full motorbike licence

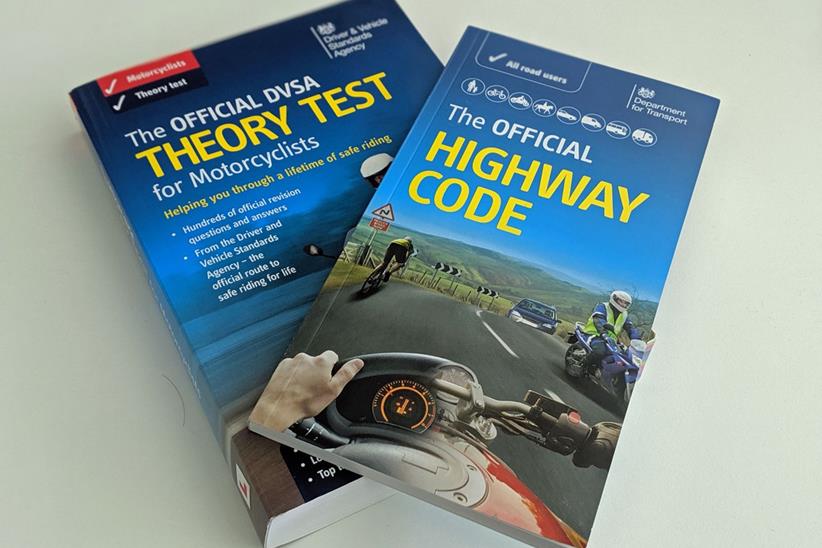

So whether you’re approaching the motorbike test as a completely new road user or like me, with some car experience, you really do need to do some revision. Luckily there are books you can buy and websites where you can take mock exams, so you feel completely ready on the day.

These threw up some absolute curveball questions that definitely validated my decision to invest some time beforehand, including one about towing restrictions for motorbikes. I didn’t even know two-wheelers were allowed to tow things, such was the depth of my ignorance.

For experienced car drivers especially it’s imperative you spend some time on the hazard perception element, because I guarantee you will be worse at it than a first-timer. A week or so before my theory test I decided to do some practice runs, ignoring the warm-up scenarios at first, just going straight into the test – and failed spectacularly.

Why? Because I was clicking every other second. Child on the pavement not holding their parent’s hand? Hazard. Car waiting at give way line? Hazard. Faulty street light? Hazard. Cars parked too close to a zebra crossing? Hazard. Bong. You’ve failed. When you drive a car you learn to see hazards everywhere, and even more so on two wheels.

But the aim of the game is to spot the developing hazard, as in, not something that could be dangerous, but something that is imminently dangerous. You’ll know when you see it. And if you click too much, the computer thinks you’re cheating and boots you out.

Come the day of the test and I was genuinely nervous. To make matters worse once inside the test centre I had to lock away my phone so I couldn’t even distract myself with work emails or (more likely) Lord of the Rings memes. Just a blank wall to stare at and my own internal monologue for company.

You complete the test sat in front of a computer screen in a roomful of other hopefuls and you have absolutely ages to answer all the questions. Take all the time you possibly can to go over and over your answers and make sure you’re read the question properly and are happy (ish) with your answer.

The hazard perception part takes place at the same screen and if you’ve practised enough you should fly through it. Or, if you’re like me, you’ll click too many times and fail one of the scenarios. I was convinced I’d ballsed it up, and was subsequently much more relaxed for the rest of the test.

Clearly that had a positive effect on my performance because despite those self-doubts I actually managed to pass – with one incorrect answer on the theory test (arghh!!!) and a less-than-perfect but adequate hazard perception result. As well as scoring zero on one scenario (the too-many-clicks one) I got three points on one and then fours and fives for the remaining 11.

Walking back to the car clearly delighted by this a stranger asked if I’d passed and then high-fived me (pre-covid Peterborough for you) before I celebrated my result in the way I thought 17-year-old me would have liked to – I texted my mum, and then went to the pub. Onwards!

Mountain bike to motorbike: tackling the CBT

First published 06 August 2020 by Adam Binnie

The CBT (or Compulsory Basic Training, to give it its full name) is a day’s tuition that most of us will have to undertake before heading out on anything two wheeled – it’s essentially the bare minimum of training you need to safely practise riding on the roads ahead of taking your full motorbike test.

Hilariously, when I did mine aged 32-years-old, I was twice the minimum age of 16, and had been driving a car for nearly that many years, plus pedalling for many more.

I assumed all that experience on two wheels and four would be an advantage, and in some ways it was, but in many, many more it absolutely wasn’t. You may have noticed that this is becoming a bit of a theme.

What is the CBT?

![]()

We’ve covered this comprehensively before but to recap, there are five elements that you can break down into three main activities – wobbling around at low speed in a car park, learning theory in a classroom, and then taking all of that out onto the road with an instructor.

If you’ve got eight minutes spare and want to laugh at me doing the former then my efforts have been immortalised in a video, where I commit loads of newbie errors like leaving my indicator on after a turn, putting both feet down when stopping and using about 9,000rpm to pull away.

Anyway, if you’re anything like me (I watched about a dozen videos and read as many articles on the CBT before the big day) then you’re here to get an insight into what is quite a mysterious process, so I’ll put your mind at rest by stating outright that the CBT is not a test, you can’t fail it (although you can be asked to come back for more training), and your instructor won’t be expecting Michael Dunlop levels of natural riding ability.

What are the classroom sessions for?

Here you’ll be taught about all the equipment you legally need and the stuff you don’t legally need but should have anyway. On that point, you might not have all your own gear yet, and while the centre I used (Wheels Honda in Peterborough) had a stock of clothing to borrow, I took my own gloves and boots because I figured it was worth having familiarity in the bike’s main contact points.

You’ll also head back into the classroom before the road ride to discuss lane positioning and what the main hazards are, plus the legal things you need like insurance, an MOT and L plates. I suspect this is also a chance for the instructor to gauge whether you’re going to be a liability, or worse, a bit of a weapon, when faced with actual traffic.

We spent a while chatting about the main cause of a crash (rider error, not other people) and how to deal with mistakes made by other road users. Remember that you have two ears and one mouth for a reason during this bit.

This brings me neatly onto what I think is the most important lesson I learned that day, and it’s something that still echoes around my head while riding now – it doesn’t matter that it was your right of way when you’re in hospital.

When you drive a car you exist in an ecosystem where (almost) everyone follows the rules and it’s so unusual for them to do otherwise that you start to give less concern to potential hazards like other road users waiting at a give way line, because you can be fairly sure they’ll give way. This is not how you ride a motorbike.

I’d already got a sense of this from riding push bikes on the road (when it’s rarely your right of way, even when it is your right of way) but it’s worse on a motorbike which is barely more visible and likely to be travelling at higher speeds. So the car at the junction should stop, but that’s assuming the driver has seen you – if they haven’t and drive into you, then the lines on the road aren’t worth the paint they’re drawn on with.

What about actually learning to ride?

This is the fun bit – or the funny bit depending on your outlook – and starts with a chat about basic maintenance and how to check the bike over for things like flat tyres or low fluid levels. Just like my pre-mountain bike rides, you use the ‘M’ test (draw a line from the front wheel to the bars, back down to the middle of the bike, then up to the brake light and back down to the rear wheel) to help locate all the things that need a once over before you head off.

Then there are some basic manual handling skills off the bike; how to move it around and put the stand down, why you shouldn’t grab a handful of brake with the bars turned (spoiler alert, it’ll fall over) and how to get the steering lock on and off. The weirdest bit for me was (and still is) the fact I can’t pick the front or rear wheel up to make tight turns like I do with my pedal bike. Even now I catch myself pulling on the seat strap while manoeuvring into my garage. This doesn’t work.

Low speed manoeuvres next, but first you have to get your head around setting the gas and finding the clutch’s biting point, made more complicated for me by the fact the lever is where my push bike’s rear brake is located, while that has been moved to a numb-feeling peg by my right foot. Also weird is the length of the levers – my bike’s are one-finger pull, the Honda CB125R’s need a whole hand.

![]()

It’s worth taking your time with this part before moving on, because working the gearshift and bite point and getting your head around how quickly the engine revs up are all vital pieces of the puzzle, and you’ll find the later exercises like doing a turn in the road or a figure eight much easier with the early lessons committed to muscle memory.

Coming to a stop and working out the timing of putting a foot (or both) down on the ground was also alien – on my mountain bike I can balance while stationary with both feet on the pedals (called a track stand, and even after lots of practise, I’m still crap at it) while doing the same on a motorbike would end up with it on the floor, because once it starts to lean sideways it’s a hard thing to rescue.

Still, at least my balance when moving was good thanks to my previous experience on two wheels, except for when it came to turning, when I quickly learned I was leaning in the wrong direction. To get my mountain bike around a tight right hander, I tip it over to the right and put all my weight on the left pedal to push the tyre’s knobbly shoulders into the dirt. You do the opposite on a motorbike, leaning into the turn. This still sometimes catches me out now.

Balancing the front and rear brake is something that would be unusual for most car drivers but again it’s something I’m used to. That said, my usual technique of leaning hard on the front brake for big stops and dragging the rear to avoid speeding up on steep downhill trails wasn’t particularly transferable, and required a bit of finesse on a motorbike. This isn’t helped by the fact the rear brake lever feels like an on off switch and doesn’t give as much feedback as the front brake lever.

On that note, I found the gearshift very hard to feel under my left foot at first, and put this down to being new to the sensation. It was only when I mentioned it to my instructor that he realised it was bent inwards slightly – when it was pulled straight it was much easier to use. It’s definitely worth flagging anything you find uncomfortable up, because it might not just be down to a lack of experience. I’ve since adjusted the gear lever on my motorbike (using spanners!) to better accommodate my comically large feet and the difference in ease of use is marked.

So my takeaway advice for this section of the CBT is take your time, don’t be afraid to mention anything you’re finding difficult and if you’ve spent a lot of your life riding push bikes, try to pretend like you haven’t.

And then you head out onto the road?!

![]()

Yes! In what felt like barely enough time to get over the fact motorbikes don’t have seat belts (genuinely a really weird sensation) we were out on the actual road with actual cars on it. My first impressions? How fast 30mph feels on a bike, and how much more I was looking around – forwards, backwards, over my shoulder, and into the eyes of drivers waiting at give way lines.

Riding a motorbike feels like operating a piece of mechanical equipment – you might think that’s an odd observation but if you drive a modern car (especially an automatic) you’ll know how far away from the actual process driving has become. It’s essential to take enough time to allow the various procedures of changing gear or braking to a stop to become second nature, or you’ll spend all your cognitive capacity thinking about them and there won’t be any spare to concentrate on looking for hazards.

To ease this process we started out on a quiet corner of an industrial estate before venturing further, and even then it was a slow build-up of residential roads and urban streets, rather than going straight in at the deep end.

Weirdly, with good tuition it all sort of slots into place quite quickly, and before I knew it I was negotiating roundabouts, merging with 70mph traffic on a dual carriageway, and leaning into a pretty brutal crosswind blowing over the flat fields of Cambridgeshire.

If you’re nervous about this part then here are some words of encouragement – after watching the video footage from my instructor’s camera it’s pretty clear how hard he was working to keep me safe. Constantly moving around behind me to ensure drivers could see us and nudging me in the right direction with his intercom – it might feel like you are on your own on the road but the reality is very different.

And that was that – after a very full-on day I was given my CBT certificate and left to try and remember how to drive a car, something that all of a sudden felt like a much easier process than it did that morning.

Learning to ride: from MTB to motorbike

First published on 28 February 2020 by Adam Binnie

![]()

Learning to ride a motorbike is a challenge weirdly harder than the sum of its parts. If I can ride a mountain bike and drive a car with a manual gearbox (obviously not at the same time) then surely it’s not a huge leap to combine those skills on something like this Honda CB125R. Surely.

If you’ve been through this process already, you won’t need to see me wobbling around a car park to know just how wrong that assumption is. If like me you’re hoping to upgrade from pedal-power to petrol, trust me, you’ll need to forget nearly everything you already know about bikes.

I’ve been on two wheels for about as long as I’ve been able to stand, from balance bikes to BMXs and then mountain bikes – crap ones from the 1990s, heavyweight downhill sleds of the 2000s and modern day do-it-all enduros. Bikes have featured since the day I denied my parents that sepia-filter moment of teaching me to ride without stabilisers by bombing past our house on my older friend’s bike, straight into a hedge. I’ve been looking for bigger and bigger hills to crash on ever since.

What sort of bikes do you ride?

It’s only ever been mountain bikes really – I’ve got nothing against roadies but my idea of riding involves finding thrills on steep gradients with roots and berms and jumps, plus if you go to the right places, a van to drive you back up to the top again. I am properly, monotonously obsessed by this, to the point of boring anyone who’ll listen to tears about my last ride. But even so, I’ll acknowledge that push bikes are seriously flawed by the need to pedal.

![]()

So, I suppose then it’s with some inevitability that I would eventually want to ditch leg power altogether and get a motorbike licence. My Dad’s ridden big bikes his whole life, often daily as a means of getting to work, so it’s something I’ve always wanted to do.

My first time riding a motorbike was oddly similar to my first driving lesson – in that a large part of it was spent faffing about trying to balance the clutch and gas to move off without stalling.

This is harder than in a car because if you get it wrong you might fall off. There were other struggles I’ll get to later, but my main take away from that experience was that contrary to popular belief, it appears you actually can forget how to ride a bike.

What are you strugging with?

It’s the little things that catch me out – not the fact that my rear brake is now foot operated, and the lever that would normally pull it is the clutch – but moments like when I pushed this Honda into my garage and to help make the 90 degree turn I tried to pick the back wheel up. Or once when I forgot what I was doing and stood up on the pegs while going over a big speed bump.

Every now and again though my fear levels drop and I realise I’m enjoying the ride – my heart rate is racing not because I’m pedalling hard but because this is brilliant, this is exactly how I thought it would be, this is like flying.

![]()

I think this is because just like riding my mountain bike and exactly not like driving a car, motorcycling requires you to move around, side to side on the seat or ducking down between the dials to breach 55mph in a headwind. The latter may well be a 125cc thing, but either way, you don’t so much feel part of the process but the entire process itself.

Plus it sounds good, this one-cylinder mini-bike that has about as much power as my lawnmower somehow sounds more emotive than most new cars I’ve driven; they’re getting so refined they don’t feel like machines at all. I know that’s a weird thing to complain about. So let’s end there before this becomes entirely too existential.

In the next instalment I’ll go into what to expect from your CBT and theory test, which, because this blog is a bit like a Quentin Tarantino film, I’ve already done. Spoiler alert.