Yamaha RD350LC at 40 - a celebration

Arguably the most loved and inspirational Japanese bike of all – Yamaha’s RD350LC – went on sale for the first time 40 years ago. And while the abilities of the 47bhp stroker twin are now the stuff of legend, the story of its creation – and of the British influence on it – is less well known.

Back in the late 1970s UK motorcyclists and the bikes available were very different. With teens-to-30-somethings dominant, the then 250 learner law made quarter-litre bikes hugely popular. At the same time lightweight sportsters were invariably air-cooled two-strokes such as Yamaha’s RD400 or Kawasaki’s KH triples with marginal twin shocks and single discs. But the LC was about to change all that.

![]()

In 1978 Yamaha was faced with a double dilemma: first, its RD250/400 was due for replacement; second, ever-tightening emissions regulations spelled the end for performance two-strokes in the USA. These factors, combined with Yamaha’s ambition to usurp Honda as World No. 1, continuing dominance of its racing TZs and dwindling RD sales in the US, led Yamaha to one crucial conclusion: the successors to the aircooled RDs would be aimed at Europe, designed with assistance from Yamaha Europe and, free of US restrictions, be as sporty and innovative as possible. In simple terms, Yamaha wanted to ‘build a TZ for the street’.

Brit Paul Butler, later team manager for the Marlboro Yamaha GP team, was, in the late 1970s, Product Planning Manager for Yamaha Europe and recalled how it came about: “Around 1977-78 we were looking to stimulate the supersports category, particularly with younger riders, with something inspired by our racing TZs. It was my job to evaluate all the information being received from the various markets and process these to put forward proposals for a new machine to Yamaha in Japan. At the time, the LC was Yamaha Europe’s main project.”

![]()

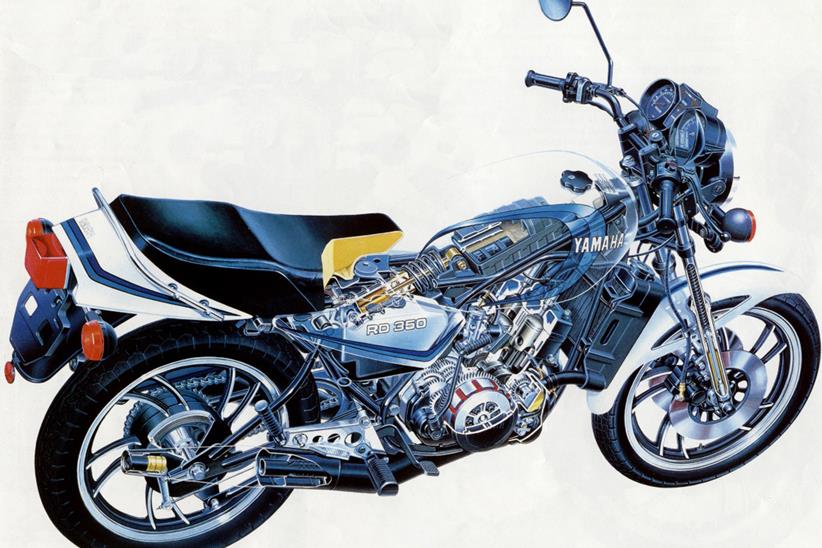

That TZ influence meant water-cooling and cantilever-type monoshock rear suspension were vital. Yamaha’s first production liquid-cooled TZ was the 1973 TZ350A, while the monoshock debuted on the TZ250C in 1976. Water jacket aside, however, in reality the LC’s new engine had more in common with the old RD than the TZ racers, with crankcases that were horizontally not vertically split and dimensions and packaging that meant RD barrels would have slotted straight on.

Even so, water-cooling enabled a significant step up in performance. Better temperature control allowed more consistent combustion, finer tolerances and thus optimum performance which, in raw bhp, meant a rise from the RD400’s 44 to 47bhp – not bad as it was giving away 51cc. The LC’s conservative state of tune would also later make it ripe for some riffler work by the likes of Stan Stephens and Terry Beckett, especially with some bolt-on ‘spannies’ from Allspeed or Micron.

Another Brit involved in the LC was former NVT stalwart Bob Trigg, one of the driving forces behind the Norton Commando. In the dying days of NVT, Trigg, along with designer Mike Ofield, was commissioned by Butler to come up with some design studies for a new Yamaha lightweight twin. “Because they wanted to keep it secret Yamaha asked for a concept for a ‘twin-cylinder, liquid-cooled 125cc boy racer’ – that was their decoy,” said Trigg later. “We came up with the designs and the ones they liked looked just like the 250 and 350LCs that came out, right down to the reverse cone expansion chambers, belly pan and bikini fairing.”

While two more Brits were long time Yamaha test rider, Dave Bean, who helped hone the prototype, and former MCN cartoonist John Mockett, who helped create the LC’s ‘italic’ wheels.

![]()

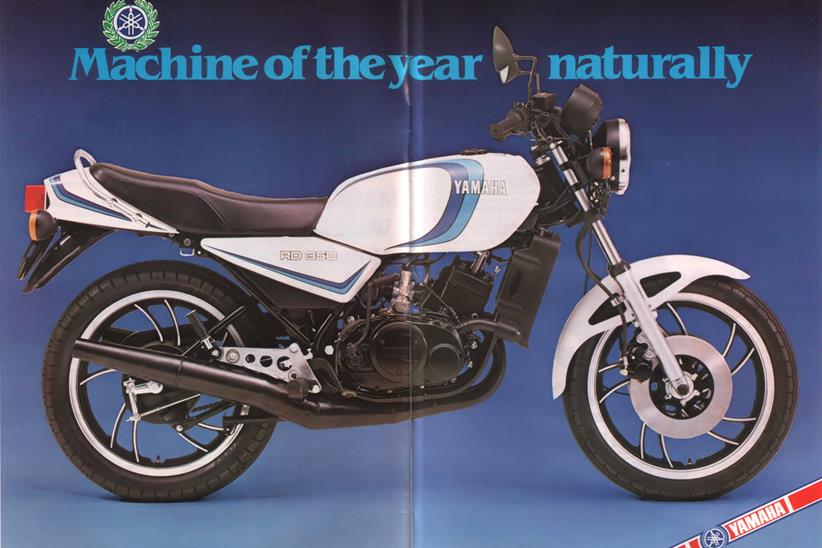

And the result, as they say, is history. In 1980 production delays only fuelled anticipation but when the bike finally arrived in June the RD350LC lived up to expectations enough to be voted MCN Machine of the Year that November.

In 1981 ‘LC mania’ grew. The ‘Pro-Am’ race series was on World of Sport and the antics of Mackenzie, Carter, McElnea et al fuelled LC fervour. A black ‘Mars bar’ liveried version was added; replica ‘ProAm’ fairings were the first mainstream manufacturer accessory fairings; paddock jackets and black visors became the ‘LC Johnny’ uniform and LCs became the most tuned and nicked bikes in the UK. It was also MCN Machine of the Year. Again.

Then, just as quickly, it was all over. The early 1980s saw lightning-fast bike development; Honda’s first liquid-cooled V4s arrived in 1982 with Suzuki’s alloy-framed RG250 and Kawa’s GPz900R a year later. Suddenly the LC looked old hat.

![]()

Yamaha responded with the fully-updated, powervalve-equipped RD350YPVS and, while undoubtedly more modern, powerful (with 59bhp) and better handling, purists will tell you it wasn’t quite the same, didn’t make the same impact or is as collectable today.

The original LC, though, had it all – looks, speed, glamour, accessibility and innovation – and it’s nice to know that, at least in some ways, it was British, too.

1980 RD350LC vs 1985 RD350N – why the LC was is so special…

![]()

With prices of good RD350LCs now £8K+ yet those of its successor, the 1983 YPVS and particularly those of that bike’s successors, the 1985 RD350F (faired) and RD350N (naked) still under £5000, it’s worth revisiting both as a riding experience.

On the LC everything is stripped-back, raw and charmingly basic. When you kick it into life you have to move the footpeg out of the way. There’s a lack of plastic covers and the motor is brimming with character.

With its lack of bottom end, the LC engine does virtually nothing until it hits its power band, at which point things get frantic as you desperately try to keep the tacho needle above 6000rpm. It’s an all or nothing riding experience that encourages stupidity. It may only have 47bhp but it makes you giggle due to its on/off light switch power delivery.

The 350N, on the other hand, is a far more civilised and refined. There’s no need to move the footpeg as the kick start easily clears it. At standstill it sounds just as eager as the LC when you blip the throttle, but once you let the clutch out there’s more low-end drive that merges into a mid-range that, while containing a bit of a zing, hasn’t the LCs abrupt change in character.

![]()

In many ways the powervalve is more four-stroke in character which makes it less amusing, lacking the LC’s wild edge, a major factor, I’m sure, in why the YPVS isn’t as popular as the LC with collectors today.

If you’re after a bike for sunny Sunday laughs that makes you smile, the LC delivers. It isn’t easy or relaxing to ride and its chassis is a little nerve wracking, but it rewards with a ride reminiscent of being an out of control teenager many years ago.

The YPVS, on the other hand, is more just an old bike that while its engine has a bit of two-stroke character, it isn’t as pronounced at the LCs – and that’s where it’s missing out. Against a modern bike the LC is skittish, wobbly, lacking drive, smelly, dirty and a touch disconcerting when you up the pace. But that’s what makes it so special and is why it will still be talked about with reverence in another 40 years’ time.