Boxing clever: BMW R18's engine was 100 years in the making

The 1802cc air-cooled unit inside the new BMW R18 is the largest and torquiest boxer they’ve ever built. It sets a whole new standard in modern, air-cooled engine design but the basic layout stretches back exactly 100 years.

BMW started life as Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (Bavarian Planeworks) in 1916 and specialised in aircraft engines. After Germany were defeated in World War I, their military were disbanded and the Treaty of Versailles was signed to prevent the country from rebuilding their armed forces.

Related articles on MCN

Bayerische Flugzeugwerke were forced to change direction and in 1919, they built the M2B15, 500cc side-valve flat twin engine with the intention of it being used as a stationary engine to power machinery. Local motorcycle maker Victoria AG bought the M2B15 and used it in their KR1.

Fancying a piece of the action, BFW built their own bike and called it the Helios. Less than a year later BFW merged with a local firm called Bayerische Motoren Werke (Bavarian Motor Works) and BMW AG was formed.

BMW inherited the BFW Helios and set about trying to improve on it. The Helios was a copy of a 1914 Douglas, so the engine was mounted longitudinally, enabling a simple final drive. The downside was that the rear cylinder suffered from terrible cooling issues, such that BMW’s then head of design proposed the best way they could improve a Helios was to throw it in a canal.

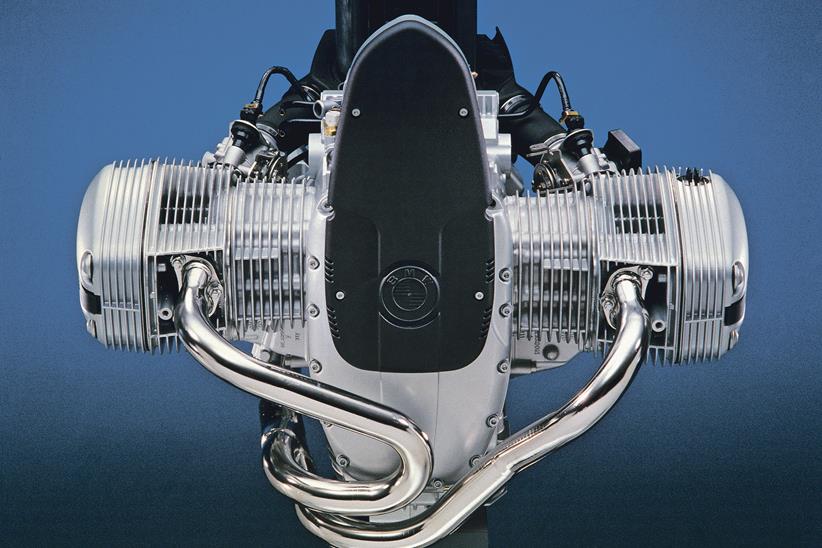

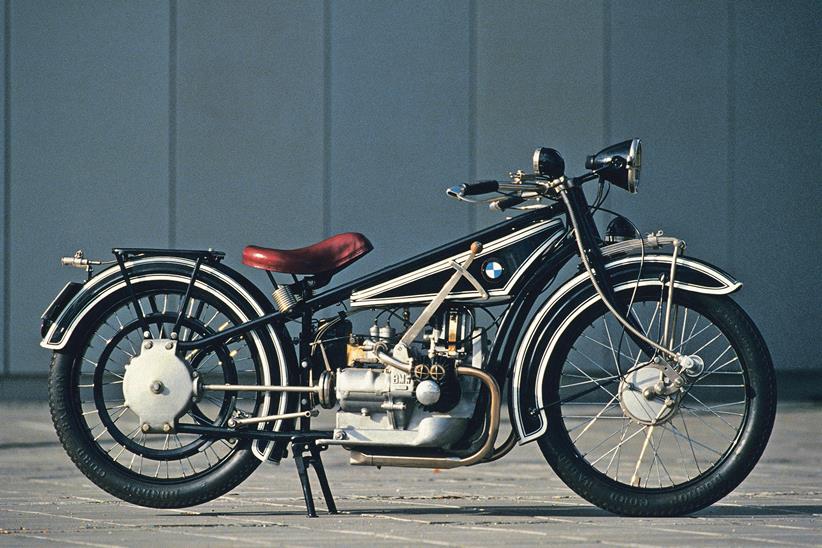

After a bit of thought he proposed a short-term solution: spinning the engine 90 degrees so that each cylinder sat in the wind. Then to get the power down, he suggested a shaft drive, with a 90-degree bevel at the rear wheel. The test was a success and BMW put the bike into production in 1923 as the R32.

Solid foundations

![]()

The R32 was a hit and laid the foundations for future BMWs. When it was first released, is was revolutionary in ways that now seem quite banal. It ran a wet sump for instance, so oil could be dripped onto the crank bearings, rather than the total loss systems common at the time.

BMW’s next big step was with the R37, which had overhead valves, followed by the R5, which brought with it two camshafts and the first foreign win of the Senior TT in 1939. The design of the R5 set up BMW’s boxers for the next 30 years and went on to become the inspiration for the new R18.

Fast foward to the ’60s and ’70s and with the notable exception of the then aging R69S, BMW’s twins became seen as old-fashioned and expensive tourers. Worse, their shortcomings were being exposed by a new breed of Japanese superbikes that were proving increasingly popular in the US market.

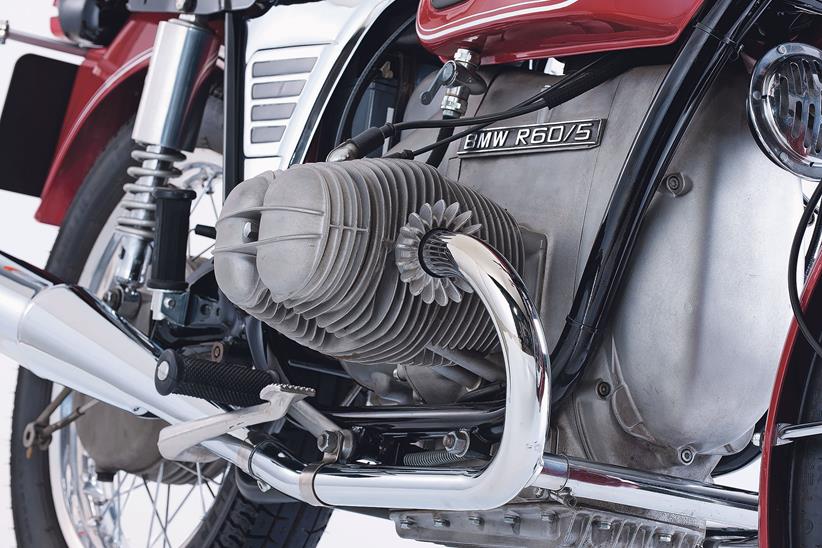

![]()

In response, in late 1966, BMW set on a course for a radical overhaul: along with the decision to can the small capacity singles and relocate to Berlin, the marque began developing an all-new family of bikes. Former Porsche designer Hans-Gunther von der Marwitz headed up the project.

He wanted to follow the tradition of former BMW racers Rudolf Schleicher (who created the R5) and Alexander von Falkenhausen by using race technology to create a new BMW that was not only fast but also reliable.

What he came up with, while still being a classic air-cooled boxer with shaft drive, was also one with a host of tech innovations, fundamentally lighter and better performing than before yet maintained the BMW values of quality, durability and comfort.

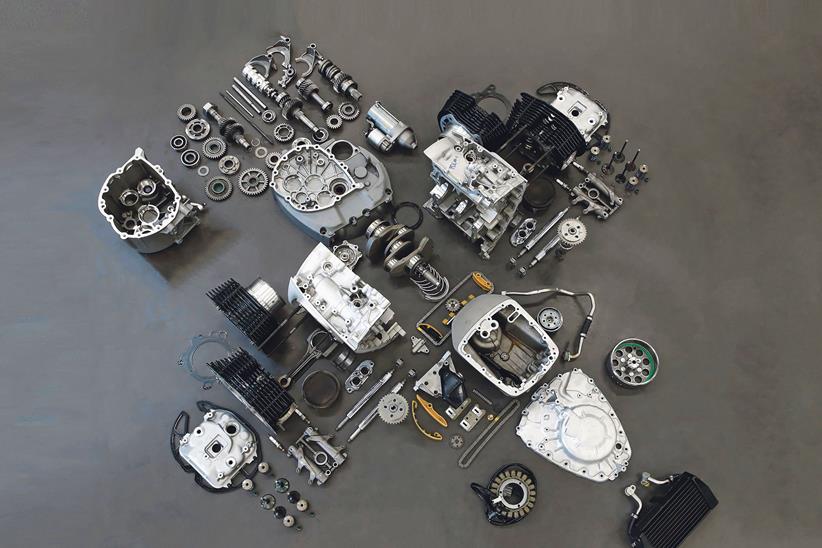

A truly modular engine

![]()

Development of the new engine, designated the Type 247 but commonly known as the ‘airhead’, was overseen by von Falkenhausen and Ferdinand Jardin with the result considered the first true ‘modular’ BMW engine. Three new bikes would use the new engine and form the /5 range with the main difference being the bore size, changed according to capacity.

Equally important was a desire to make the air-cooled boxer look more modern. New, taller, one-piece aluminium crankcases rose right up to the fuel tank and now contained an electric starter motor. There was a new one-piece forged crankshaft running in plain bearings.

While the pushrods were now placed under the cylinders to leave the top of the barrels free from clutter and allow greater airflow across the cooling fins. This was achieved by placing the camshaft under the crankshaft.

Weight-saving aluminium was now also used for the barrels but with cast iron sleeves. The gearbox, meanwhile, was a new four-speed, three-shaft unit bolted onto the rear of the engine. During 1970, 12,346 examples of the /5 series were sold – the best overall production figures since 1955.

Over the next 24 years, the 247 engine steadily grew in capacity until the R1100RS was launched, powered by the new R259 oil-cooled 1085cc engine.

Birth of the ‘oilhead’

![]()

The 259 ‘oilhead’ brought with it some big changes, most notably the use of fuel injection and four-valve heads but there were other changes too. The central camshaft was chucked in favour two small camshafts that ran under the cylinders, operating the valve train via small pushrods – a set up that remained until the dual-overhead camshafts arrived with the 2010 ‘twin cam’ update.

Even through the water-cooled update and into the ShiftCam, the general layout has remained true to the /5 from 1969. Until, that is, the new R18 arrived, which has cherry-picked various bits from their engine history, with a few modern extras, to create something really special.

In simple terms, not only is the styling of the R18 heavily based on the R5, the engine layout is also broadly the same. In the new R18 the crankshaft once again sits lower in the engine block, with two camshafts above acting on the valve gear, so the classic over-the-top pushrod tubes have returned.

![]()

Interestingly Sepp Miritsch, Head of Air Cooled Boxer Series (who designed the HP2 engine) says half the reason BMW went to a single cam back in the 1960s was to save money. Unlike the R5 though, the R18 has four valves per cylinder, operating off two pushrods (a sort of R5, /5 and R1100 hybrid).

It’s also a pioneer of new tech for BMW, with the fuel injectors placed in the head firing fuel straight past the intake valves into the cylinder for a cleaner burn. So there you have it. One hundred years of development and we’re back to using ideas from the 1930s. Some things just never change.