The TT that became a Nazi propaganda coup

It’s been described as motorcycle sport in its purest form. But the Isle of Man TT hasn’t always been just about sport.

In 1939, the world’s most spectacular motorsports event became a propaganda exercise for the Nazis.

With Czechoslovakia and Austria already under German control, and war with Britain looming, the Nazi propaganda machine viewed sporting victory as a means of demonstrating international dominance. A victory at the TT, at the time the pinnacle of motorcycle sport, would be a coup.

In the official TT database of race records, the entry for the year says: ‘As war clouds gathered in 1939, the German government was determined to boost national prestige by dominating every international sporting event, and the TT races were no exception.’

Less than three months before the start of war, German riders with Swastikas on their leathers arrived in Douglas to stamp their dominance on the annual races.

Six of the riders – Ewald Kluge, Heinrich Fleischmann, Karl Bodmer, Wilhelm Herz, Otto Rührschneck and Karl Gall – were stormtroopers in a paramilitary organisation run by the Nazi party.

The National Socialist Motorised Transport Corps, or Nationalsozialistische Kraftfahrkorps (NSKK), existed to motorise the German military by training drivers and riders.

The other two riders – Siegfried Wünsche and Georg Meier – were soldiers in the German army.

Kluge, Fleischmann and Wünsche were riding for DKW; Bodmer, Herz, and Rührschneck for NSU; Meier and Gall for BMW.

Kluge was an NSKK Sturmführer, or assault leader, and had been a member of the Nazi party since 1937.

The riders were accompanied by Erwin Kraus, who was introduced in the Manx press as a representative of the German equivalent of the Auto-Cycle Union, the sport’s government body in Britain.

But Kraus did not hold a civilian post. He was a senior Nazi Party official and head of the NSKK. The paramilitary organisation had taken over all German motorcycling and motoring clubs in 1933, effectively seizing control of motorsport. Subsequent international motorsport events had been treated as Nazi propaganda exercises.

The NSKK had brought with it its Nazi philosophy, spelling an end to the careers of ‘non-Aryan’ riders, who were not permitted to compete. Leo Steinweg, a successful former DKW factory rider, had been forced to flee Germany because of his Jewish background.

NSKK Obergruppenführer Kraus moved in the highest circles of the Nazi Party, appearing publicly with Hitler at motorsport events.

Not everyone accepted the German effort on purely sporting terms. But Kraus proved capable of silencing critics.

Isle of Man Weekly Times editor George Brown wrote a lead article attacking Hitler and criticising British riders competing for German and Italian teams.

Brown wrote: ‘Of course we don’t want German or Italian riders to win and still less do we desire a victory for a British rider using a German of Italian machine… There is more than a chance that the countries these famous British riders represent will be at war with Britain before the year is out.’

Brown was sacked from a post as a BBC radio race commentator as a result of his outburst.

A letter from the BBC’s regional programme director informed him: ‘We feel it would be most inadvisable at the present time for us to be associated with an element of political controversy in what we feel should be regarded purely as a sporting event.’

In his book The Nazi TT, Roger Willis suggests the BBC ‘had been bullied into ditching Brown’ by Kraus.

Kraus had complained to his ACU counterpart, who referred the matter to a senior UK government representative on the Isle of Man, Lieutenant Governor Vice Admiral William Leveson-Gower.

DKW PR man and Nazi Party member Karl Kudorfer told a newspaper: ‘The protest was lodged because we took exception to remarks about Herr Hitler.’

Willis writes that Kraus, Leveson-Gower and the BBC’s TT producer, Victor Smythe, had dined together. ‘It is likely that Leveson-Gower… simply had a word with the BBC,’ he says.

The stage for the Nazi propaganda coup was cleared.

All three German marques had despatched state-of-the-art works race bikes. BMW had brought its supercharged 500cc 255 Kompressor. The boxer-twin made nearly 70bhp – much more than the British singles of the time. It was also lighter than British machines.

Meanwhile Norton had initially decided not to compete at all because of a commitment to a military contract. The factory had eventually changed its mind and sent 1938 machines for Harold Daniell and Freddie Frith to ride.

Velocette had answered BMW with its own new supercharged twin, the Roarer, conceived and developed in under a year – and reportedly still being assembled on the ferry to the Douglas.

The German teams were denied in the Junior race by Irishman Stanley Woods, who claimed his 10th and last TT victory on a Velocette. Daniell finished second on a Norton and Fleischmann third on a BMW. Frith had led until the last lap, when his Norton had developed engine problems.

The Lightweight race, held in poor weather, brought a surprise win for Ted Mellors on a Benelli single, the Italian factory’s first ever TT victory. Kluge finished second on a DKW.

According to the TT database, ‘Everybody, both on the island and in Germany, was waiting for the Senior and the clash of the supercharged BMW twins and the all-conquering British singles.’

The BMWs had put in a fast practice session, reaching a top speed of 135mph. Georg ‘Schorsch’ Meier had achieved the fastest practice lap, at 90.27mph. Jock West, a British rider in the BMW team, was third place on the leaderboard behind Stanley Woods on a single cylinder Velocette – the Roarer twin had not materialised.

But one of the BMW team – Karl Gall – had suffered injuries that would prove fatal. Gall crashed on his first practice lap at Ballaugh Bridge on June 2. He died on June 13.

Meier and West decided to continue. When Friday’s Senior race came, the weather had transformed to dry and sunny.

The previous year’s winner and outright lap record holder, Norton-mounted Harold Daniell, was soon passed by Woods.

Woods and West were neck-and-neck. But Meier was 52 seconds faster than either on the opening lap, with a 90.33mph average speed from standing start.

On lap two, West took a five second lead over Woods and Meier went even faster, with an average of 90.75mph.

West increased his advantage over Woods in lap three, storming to 15 seconds ahead. Then Woods lost time in a fuel stop, when his engine took more than half a minute to fire. Meier was now a minute-and-a-half in front after matching his opening 90.33mph lap.

By lap five, Woods had lost third place to Frith and regained it again. But Meier proved the fastest again. He pulled to two minutes ahead of second-placed West and more than three minutes in front of Woods.

In lap six, the gaps between the three leading riders closed. Woods closed on West by seven seconds, but was still 58 seconds behind. It was too late.

After a fuel stop by West at the start of the seventh and final lap, Meier took first place by two minutes and 20 seconds. Frith overtook Woods in the last lap to take third place behind West.

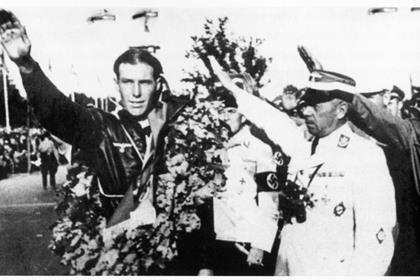

Roger Willis says in his book, The Nazi TT: ‘The ensuing winners’ enclosure spectacle was unprecented for what the mealy-mouthed BBC had insisted was a purely sporting rather than political event.

‘Team management and mechanics fell in alongside Meier and their right hands went up in unison for the Nazi “Heil Hitler” salute. A sporting gesture? Jock West stood next to Meier, looking bemused and fiddling with his gloves. The Führer most emphatically had his propaganda coup.’

Read the full story of The Nazi TT in Willis’ book of the same name, available at www.dukevideo.com and from all good book shops.